Widening & narrowing moats in Fintech

7 Powers in Fintech and building switching costs upon the foundations of network effects

Join 2,400+ Founders, Investors and Operators for weekly Missives on software strategy and technology trends below.

As always, if you enjoyed this please share it with your friends and colleagues. You can find me on akash@earlybird.com.

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers capture most of the most commonly cited vectors of defensibility in software and fintech.

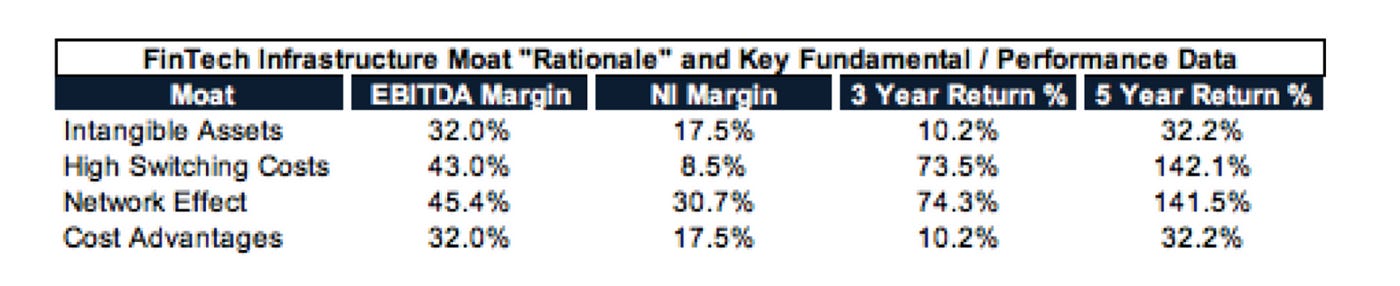

Of the 7 powers, network effects and switching costs are the most important predictors of superior margins and performance in Fintech, preserving hundreds of billions in revenue and trillions in market cap for incumbents.

Direct and indirect network effects can be observed across consumer and B2B fintech. Venmo’s utility increases in lockstep with every additional user, whilst Bill.com’s customers seeking to settle invoices benefit from their suppliers being on the network, and of course Klarna’s ecosystem of merchants and consumers both derive benefits from the growth of the network.

Last week,

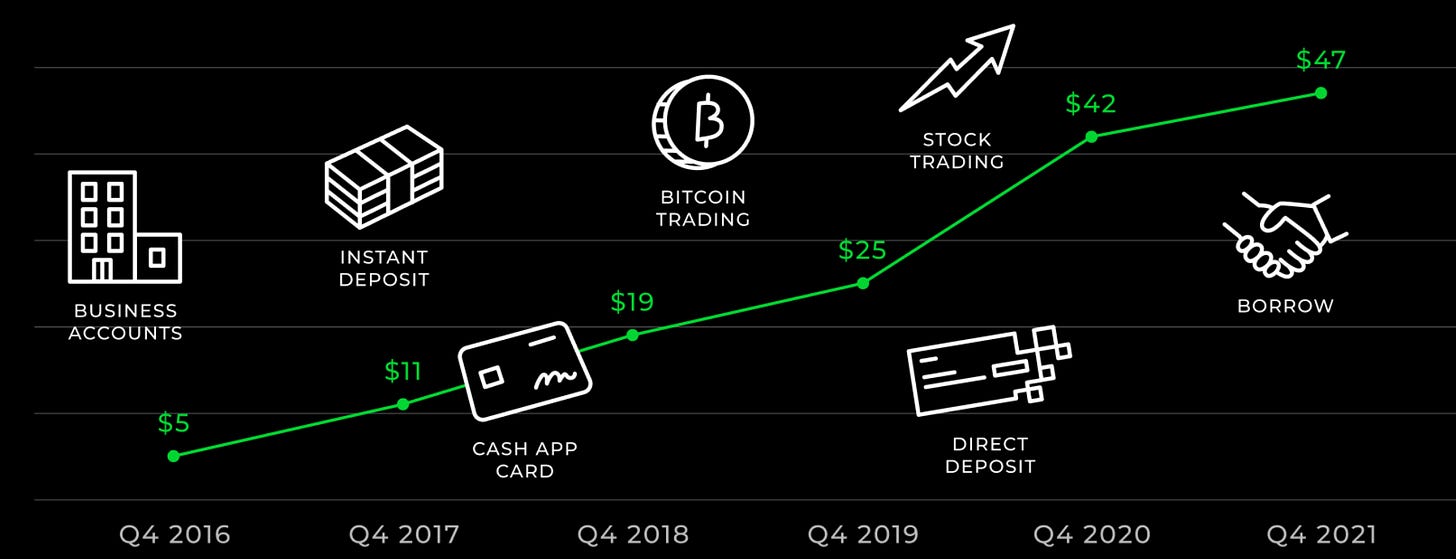

(formerly of Cash App) wrote about subtle differentiation in fintech, i.e. the notion that success in fintech is often attributable to being 2x better at many things rather than being 10x better at one thing. Cash App was 2x better at money movement, virtual card issuance, fees, and many other jobs-to-be-done.Fintechs reliant on network effects can ride this moat to scale, but the most durable businesses build upon this foundation by going multi-product and reducing reliance on network effects.

Cash App’s success over Venmo is a case study in point. Venmo’s scaling rested on serving the singular job of P2P money transfer extremely well, whilst Cash App used the P2P money transfer job as a cost-efficient customer acquisition wedge into a multi-product suite - one that, as Kunle wrote, is 2x better at all the jobs it solves for. Cash App’s own analysis suggests their CAC is $10 compared to $30-50 for neobanks and $300-600 for retail banks.

A survey from Morgan Stanley of Cash App customers found a high propensity to adopt further Cash App products; 74% would use a checking account, 68% would use a credit card, and 67% would use a savings account. Importantly, of Cash App's 51M monthly active users, 72% are Gen Z/Y; there is a window in the next few years for Cash App to seize their unfair advantage to increase the gravity of their platform by forming primary banking relationships and cross-selling to this demographic, which will eventually account for 37% of spending by 2030.

As founders go about building their businesses across the various FinTech sub-sectors think about how, if you can execute on your vision, your company can build a moat due to Network Effects first & foremost followed by the potential for Higher Switching Costs (which is earned not charged), Intangible Assets, and Cost Advantages (e.g., cross-selling products, marketplace vs. single lending source, etc…)

- John Street Capital

To the extent that business models evolve into providing fuller service to customers coming into the product, the value of the network effects becomes less important. People might come for the network, but stay for the tool.

- Giorgio Giuliani and Aika Ussenova

The sequencing of establishing network effects and building upon this to serve a range of jobs-to-be-done, and by extension increasing switching costs, applies to B2B fintech too.

Network effects of buyers and sellers being parlayed into high switching costs through product expansion, integrations and verticalisation are well evidenced in B2B payments and Accounts Payable automation software.

As

wrote, Bill.com’s product expansion has even yielded an inversion of its revenue mix from its IPO to today - 60% of its revenue today comes from transactions compared to 29% at IPO (80% of these transactions are recurring and therefore of similar quality to subscription revenues). Horizontal AP automation vendors entrench switching costs through product expansion, whilst verticalised vendors like AvidXchange go one step further with integrations to verticalised ERPs - in short, switching costs follow network effects.Although not ubiquitous, this playbook is clearly at work in different consumer and B2B fintech categories, presenting a formidable challenge to startups looking to penetrate these moats. This makes it all the more important for entrepreneurs to be aware of which moats are narrowing or widening over time.

Narrowing and Widening Moats

Network effects in AP automation software undoubtedly have a strong gravitational pull, but offering a sufficiently superior product, coupled with the right distribution partnerships, can offset these network effects, particularly for the new suppliers onboard by buyers. Melio is an example of a new entrant to the category that leveraged this flywheel to bootstrap their network in the face of existing networks of buyers and sellers. Plaid’s network effects of bank coverage were more pronounced in the US than in Europe, where regulation collapsed barriers to entry and various Open Banking aggregators developed coverage parity. Network effects, particularly in B2B fintech, are more susceptible to narrowing rather than widening.

Angles of attack on switching costs are still less well defined, as I wrote last week. The old adage of ‘no one ever got fired for buying IBM’ will likely retire in concert with the CFOs wedded to legacy vendors. A generation of tech-savvy professionals will rise to leadership positions and replace these outgoing CFOs with endorsements of consumerised enterprise SaaS, running the gamut from application SaaS point solutions for the sales team to core systems of record migrations from Workday/Netsuite and the like. One interesting thing to ponder is what cohort of enterprise software falls into the category of ‘IPO readiness’, connoting a company’s maturity in adopting trusted solutions for their tech stack. Overall, I would say switching costs is a narrowing moat, especially if one takes a long enough time horizon for a middleware engagement layer to displace the system of record.

An example of cornered resources in fintech is regulatory licenses. As I’ve been learning, regulations for payments processing in Europe remains a patchwork. Payment Institution licenses and Electronic Money Institution licenses are the two sought after types of licenses that confer the right to process payments, but each comes with different rights on holding funds and being in the flow of funds for payouts. Remarkably, there are still workarounds in different European jurisdictions - it’s no wonder fintechs capitalise on these workarounds when you consider the time it can take for the FCA or equivalent regulators to process applications nowadays. Banking licenses are equally rare, as some neobanks are finding. Fintechs often resort to acquiring companies to expedite the process of securing a license. Armed with sufficient capital, this moat is also susceptible to narrowing over time.

Adyen is probably the best example of process power in fintech. The $50bn company continues to grow at 40-60%, whilst boasting ~60% EBITDA margins, and better per-FTE efficiency than Netflix, Apple, Google, and Facebook. Adyen proudly highlights the Adyen Formula in their annual report, a set of principles that sustain the firm’s competitiveness, efficiency, and product velocity. Importantly, Adyen’s incredible R&D machine is only fully channeled at a new product once there is sufficient demand from customers, at which point it goes all in. Process power is rare in fintech but widens over time - this does not disqualify startups from acting with intentionality about their process power from day 1 and letting it compound.

Economies of scale in fintech are common, especially in payments. Once again, Adyen is a great example. Adyen has managed to continue lowering its take rate as its scale affords the company operating leverage and cost efficiencies with the card schemes, particularly when enterprises opt for Adyen’s omni-channel offering including payouts and alternative payment methods. (Neo)banks leverage the higher rates on deposits for sustained R&D. Undercutting on price as a means to land accounts before building out compelling enough software/coverage/rails to raise pricing is a viable tactic for startups, but in fintech this moat continues to widen over time in general.

These are anything but divinations on fintech moats - I’d love to hear your thoughts on what other examples are instructive, and whether you agree with these assertions.

The rule of thumb I used in fintech was that no edge lasts more than 18 months; ie from the time you launch your differentiated product that has customer traction, you have a maximum of 18 months before your competitors catch up (and from what I can tell that remains true today).

- Kunle

What I’m Reading

ServiceNow (NOW) – The Platform for Digital Business

ServiceNow continues to grow at 30% well into billions in revenue and has 20 customers paying $20m ACVs.. a fascinating case study in product expansion.

Lightspeed wrote about the transition from systems of record > engagement > intelligence > cognition, with LLMs potentially permeating up to 50% of a knowledge worker’s job. Worth pairing with this survey from Github of 500 developers on how copilots have already been showing profound gains.

Death to Revenue Multiples: Long Live the DCF!

Equal Ventures give a timely reminder that valuations proxied on revenues miss the mark when revenues are completely untethered from the most important primitive of value creation: free cash flow.

The Shadow Price of Venture Capital

Nnamdi Iregbulem crunched the data to prove that for every 1% increase in funding, valuations rise about 0.66% or two-thirds of a percent. Despite funding plummeting, valuations haven’t fallen commensurately, and in episodes of divergence in the past its the valuations that course correct.

The Myth of the AI Infrastructure Phase

It remains to be seen if AI neatly conforms to the app-infrastructure cycle first postulated by USV, i.e. that apps and infrastructure evolve in responsive, rather than distinct, cycles. The emergence of LLMOps as a category only seems somewhat responsive to pain points of application developers, and at times companies in the tooling layer seem to be building more in response to the properties of LLMs (e.g. hallucination, cost/accuracy/latency trade-offs).