Hey friends! I’m Akash 👋.

Welcome to Missives, where I write about startup strategy across software and fintech. You can always reach me at akash@earlybird.com.

Thank you for reading! If you enjoy these, please share them with your friends and colleagues 🙏🏽. Wishing you a great week!

Current subscribers: 3,260

The debate about value accrual in AI continues.

Entrepreneurs building application SaaS companies on top of foundation models face a common line of questioning from investors around defensibility, lock-in, and pricing power. Within application software, different markets can be placed on a continuum of attractiveness for net new startups.

Founders at the -1 to 0 stage, in AI or otherwise, are heat seeking missiles searching for the most attractive end markets.

‘When a great team meets a lousy market, market wins.

When a lousy team meets a great market, market wins.

When a great team meets a great market, something special happens.’

- Andy Rachleff

The science of assessing markets is as nebulous as assessing product market fit, but there are heuristics.

Mauboussin’s Market Metrics

Michael Mauboussin, Head of Consilient Research at Counterpoint Global, is an authority on market structures.

Consilience: The linking together of principles from different disciplines especially when forming a comprehensive theory.

In a paper published in September 2022, Mauboussin and Dan Callahan studied the market structures of several industries and the pricing power this confers.

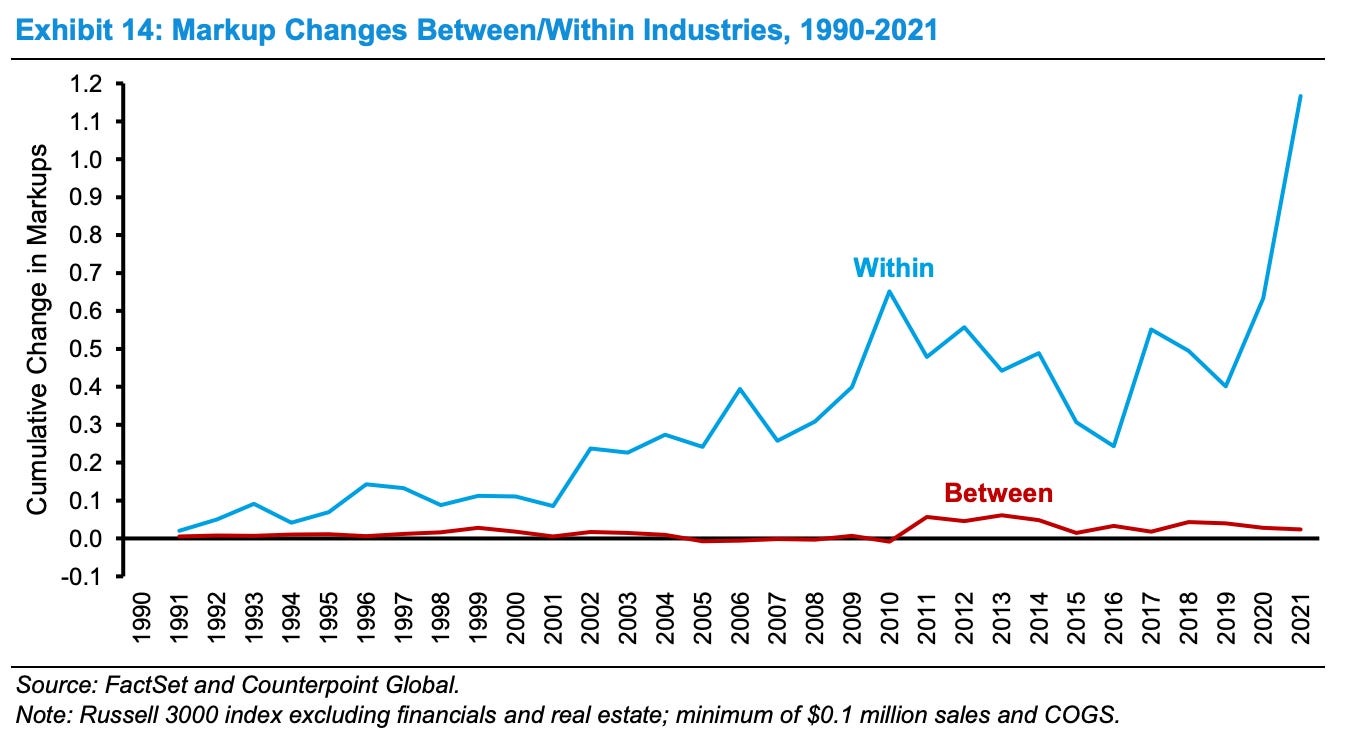

The paper first analyses the evolution of ‘mark ups’ across the Russell 3000. Mark ups are a proxy for pricing power, measuring when companies can set prices above their marginal cost.

At first glance, pricing power has sharply increased in the last three years, which is indicative of increased winners-take-most or winners-take-all markets where concentration confers monopolistic power to set prices.

Some academics have called this phenomenon the rise of “superstar” firms. The argument is “that industries are increasingly characterized by a ‘winner takes most’ feature where a small number of firms gain a large share of the market.”

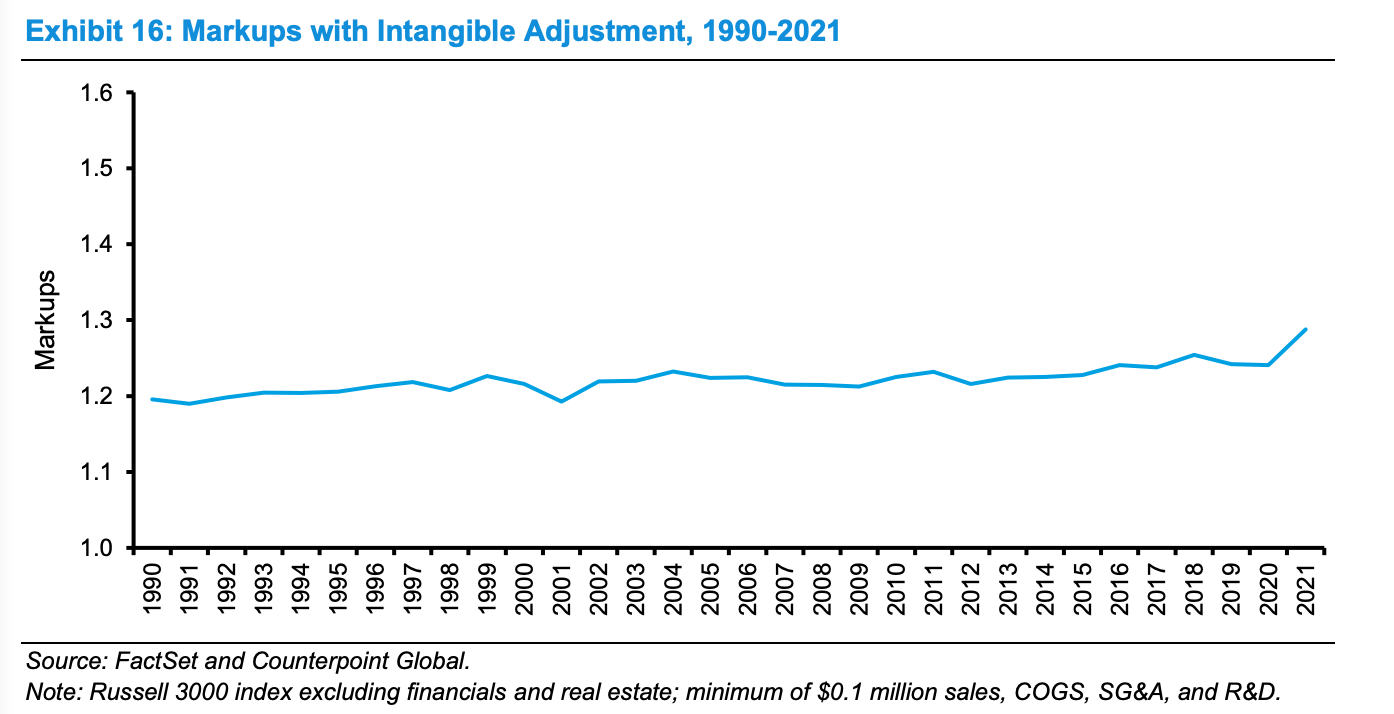

However, when accounting for investments in intangible costs (e.g. software development), this effect becomes much more muted - e.g. Snowflake’s mark up comes down from 2.25 to 1 with this methodology.

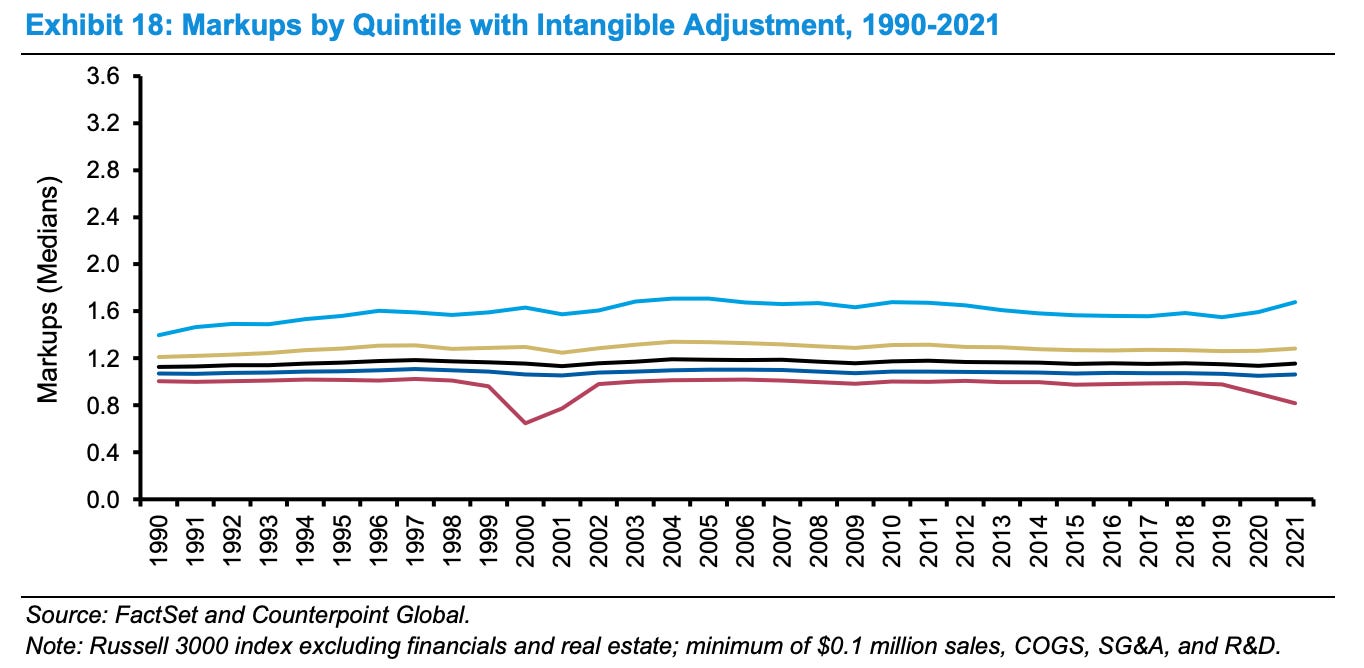

Even if pricing power has stayed largely consistent for the last three decades, there is evidence of a dispersion with top quintile firms (superstars) having a notable delta in pricing power. 40% of superstar firms are tech companies.

Mauboussin then goes on to study market concentration, the key driver of pricing power.

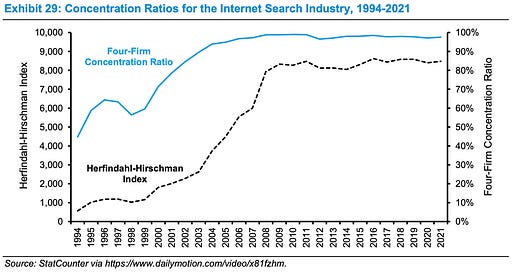

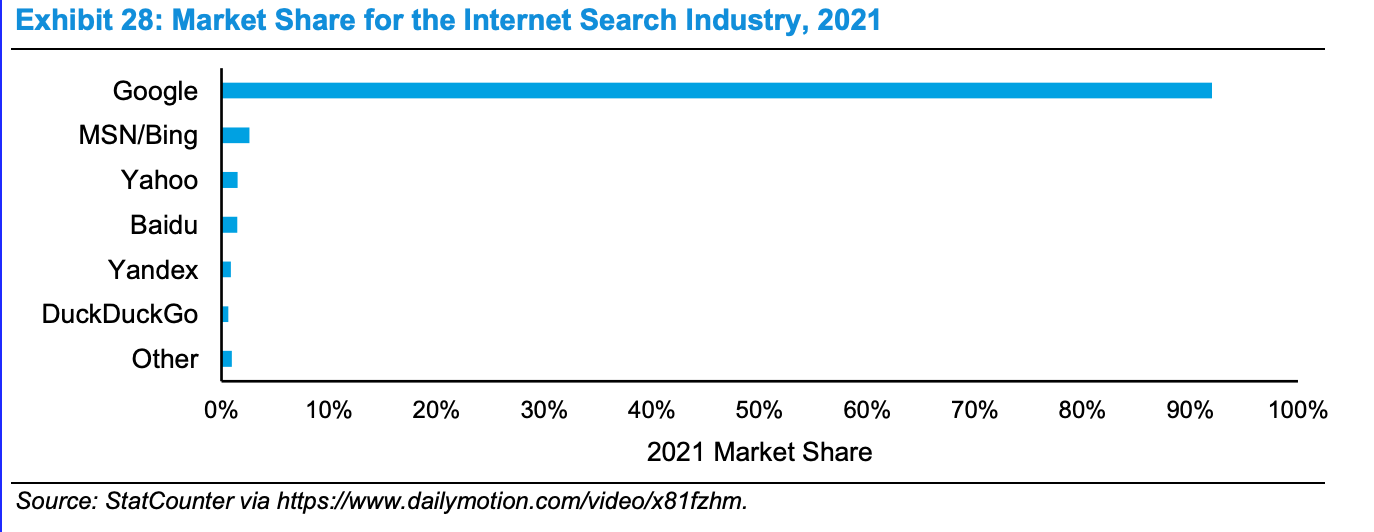

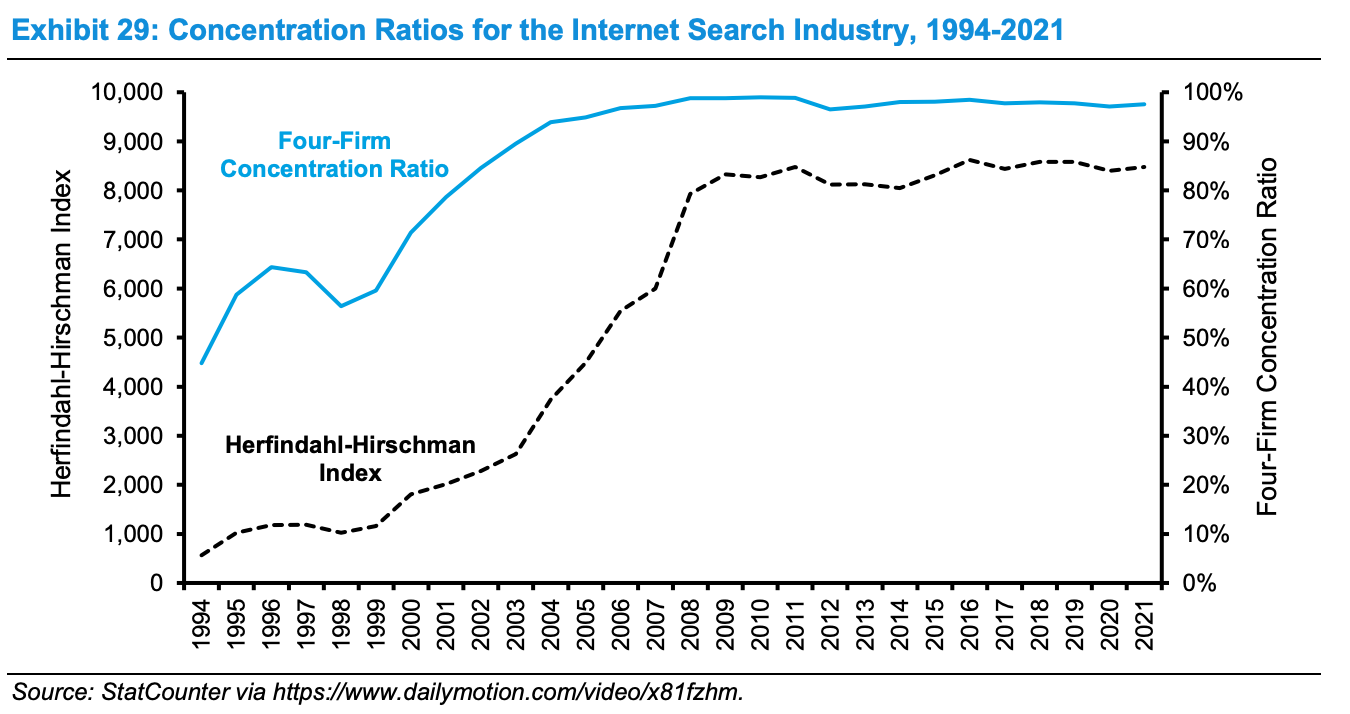

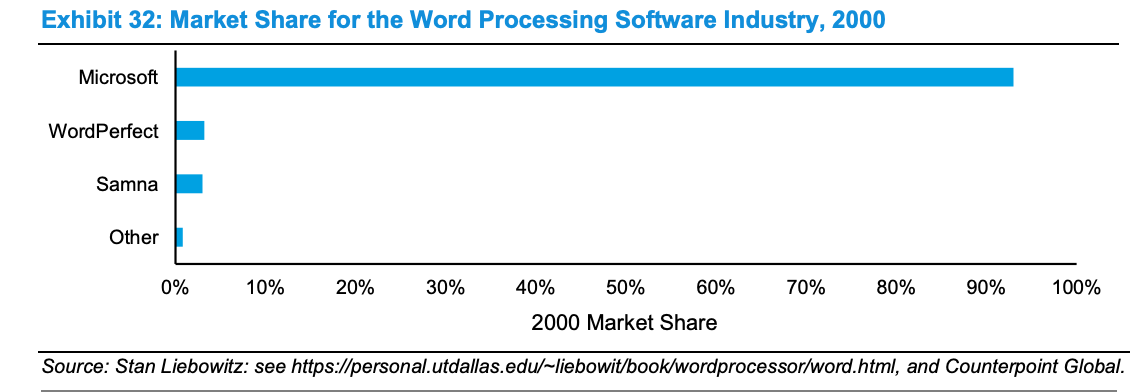

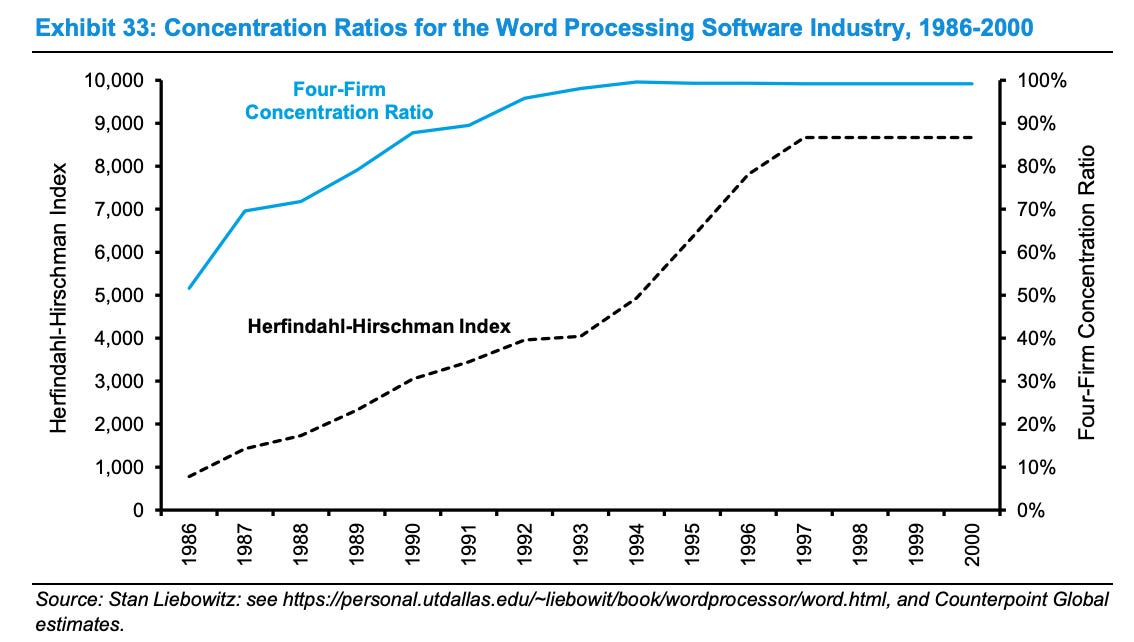

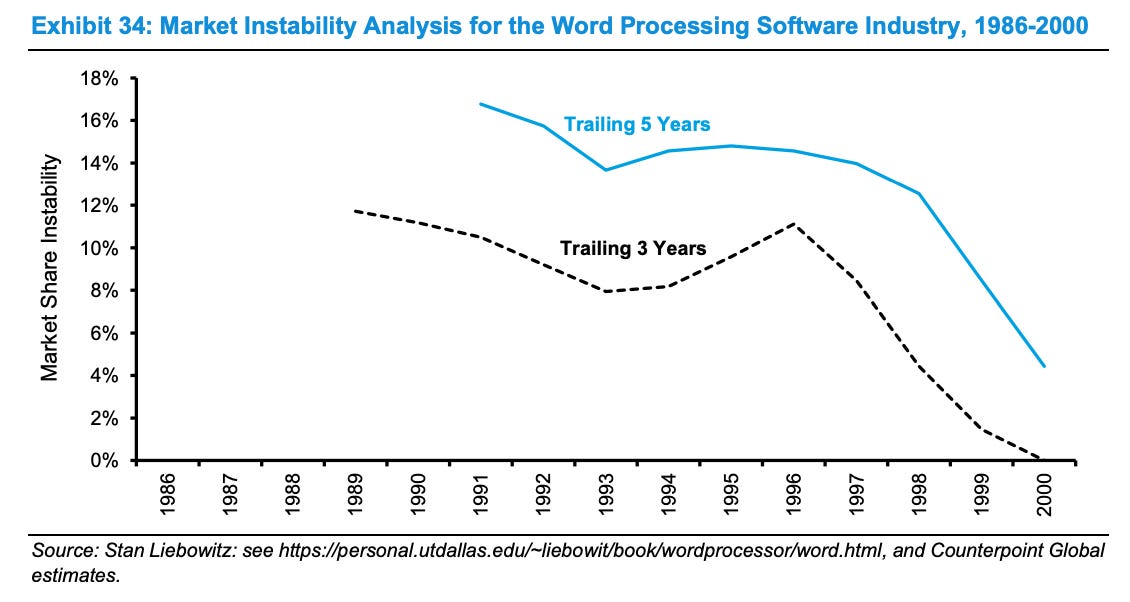

Using Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) and C4 (market share of four largest industry participants) as proxies for market concentration, Mauboussin looked at the automobile, airline, internet search, and word processing markets.

The concentration data on autos and airlines points to highly competitive markets with limited pricing power.

Search, on the other hand..

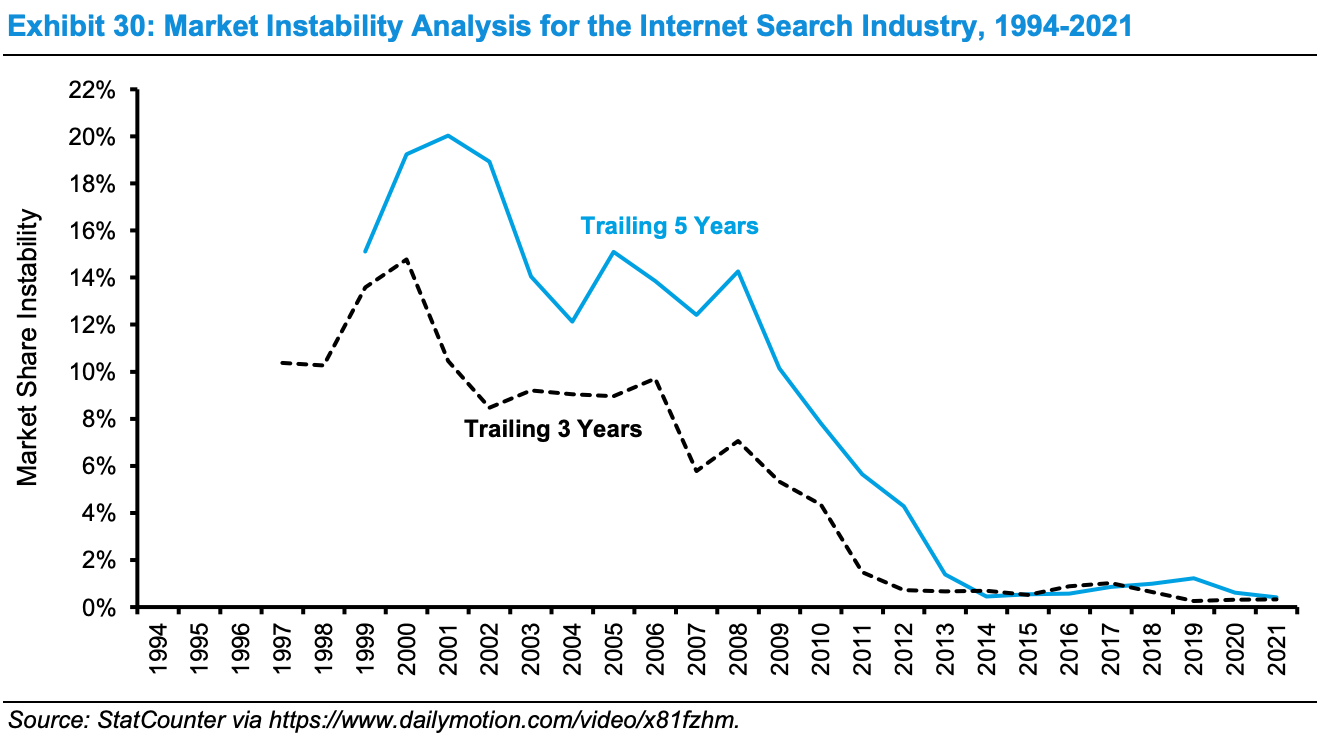

But when you decompose the process, what you realize is there was just enormous amount of shuffling happening early on. And when you think about, for example, Internet search, it was by no means a foregone conclusion that Google would emerge as the dominant player.

Michael Mauboussin

The jostling for market share between Excite, AltaVista, Lycos, Infoseek, and Yahoo leading up to 1999 gave way to Google’s ascent to unassailable market leadership.

It’s a similar outcome in word processing, which in fact started with a leader that had half the market sewn up in 1990.

WordPerfect owned half the market before Microsoft arrived with Windows and rode the secular transition to Microsoft’s operating system.

Speaking to Patrick O’Shaughnessy, Mauboussin summarises the two principles he uses to assess markets:

One is the idea of market share stability. The underlying premise here is pretty straightforward, which is it's hard to have a sustainable competitive advantage if market shares are shifting around a ton all the time.

The second one, Patrick, and I emphasize this in my class a lot, but I think that we don't do enough of this, which is simply looking at entry and exit. I think when people see the data, they're usually surprised at how much entry and exit there is.

Much like R&D leverage and multi-product greatness drive high terminal FCF margins, high market share stability and low entry/high exit rates towards the top of a company’s S-curve drive margin expansion.

Market Genes

The terminal margin expansion conferred to winners in winner-take-most or winner-take-all markets are the driver for the rich premiums that investors are willing to pay.

characterised Thrive Capital’s purported investment in OpenAI at a $80bn valuation as the most contrarian bet in venture capital. Embedded in the investment are several beliefs about the future of closed versus open source models, OpenAI’s ability to continue leadership of SOTA models, maintain its brand, and much else. Undergirding these specific reasons is a more general principle that Thrive follows on market structures:Markets go up, markets go down, but at the end of the day, if you invest in quality, that quality will ultimately compound on itself. There's a scarcity value to quality. Those that invested in Fifth Avenue a decade ago are happy that they have it today.

Our view is if you are concentrated in the most exceptional businesses and you hold those businesses over a very long time, a lot of the value in those sectors that you're investing in will ultimately accrue to the #1 player.

- Josh Kushner

Different markets have different genes.

In many categories of vertical SaaS, companies inflect once they reach c. 10% local market share - CACs come down, pipelines swell, conversion increases, and attainment improves as a byproduct of industry leadership. Veeva’s 60% market share to Salesforce’s 20% is the canonical example.

Financial services and fintech don’t exhibit winner-takes-most or winner-takes-all dynamics, despite obvious network effects, as Matt Brown has covered. As Matt admits, in lieu of winner-takes-most dynamics, ‘Fifth Avenue’, ‘Third Avenue’ and others can all become large enough in absolute terms if not relative terms, due to the size of the market.

Then there’s TSMC and its incredulous leadership of advanced semiconductor manufacturing. Those that read Chip Wars this summer will appreciate the many variables that have cemented TSMC’s indispensable role in the chip production value chain. One of the actors in that value chain is Nvidia. CEO Jensen Huang likes to describe Nvidia’s first markets as zero-dollar markets.

We prefer to position ourselves in a way that serves a need that usually hasn’t emerged.

It’s our way of saying there’s no market yet, but we believe there will be one. Usually when you’re positioned there, everybody’s trying to figure out why are you here.

Nvidia pursued (at the time) greenfield markets like automobile software, PC gaming, supercomputers, and machine learning. Category creation in software comes closest, but that is often a derivative of product marketing rather than true market creation. Having the foresight to build for a market that doesn’t exist yet confers the advantage of having the requisite infrastructure to capitalise on the market when it does arrive.

Disruptive Innovation

Software markets are undoubtedly bigger than ever. Venture dollars have grown several fold to keep up as software ate the world.

Enterprise software is still in its early innings. To be sure, conditions are different than in the early 2010s - cloud penetration is higher, incumbents possess both distribution and the technology, and the cost of growth is higher.

That said, highly concentrated markets can often be prised open by exogenous developments like platform shifts.

Characterising AI as either a disruptive or sustaining innovation has been the focus for most capital allocators these last 12 months. Snowflake ended up acquiring Neeva, but Perplexity’s fundraise signifies investor belief that foundation models represent a disruptive innovation for search. There’s a lot of nuance, sure, but some markets are large enough to accommodate multiple faiths about the world.

Midjourney, Character.ai, and Github Copilot are just a few examples of either high concentration markets being prised open or zero dollar markets that transmogrified into billion dollar markets.

Further Reading

How Can You Tell If Your Market Is A Good One?

Who Cares If It's Been Tried Before?

Reading List

Fintech in Q3 F-Prime Capital

Attenuating Innovation (AI) Ben Thompson

Getting Burn Rates in Line with Reality, Not the Letter Name of the Last Round Charles Hudson

The AI Elephant in the Boardroom Battery Ventures

Quote of the week

‘The proper reference point for burn rate is progress, not the name of the last letter round you raised. Capital is an incredibly valuable and scarce commodity today, so spend it wisely.’ Charles Hudson

Thank you for reading. If you liked it, share it with your friends, colleagues, and anyone that wants to get smarter on SaaS, Fintech and GTM. Subscribe below and find me on LinkedIn or Twitter.