We do invest globally. Greenoaks started in 2010. We invest everywhere outside China. India, South East Asia, Korea, Latin America, US, Europe, all places we've invested.

When we started Greenoaks there were about 20 million smartphones being shipped globally and we thought it would get to 100 million or 200 million. Obviously the number is well north of a billion. So, to us, the opportunity set to find what we think are great compounding franchises being built on the back of mobile phones, and on the back of the internet, is a global opportunity. We think that the characteristics that define great companies globally are universal, not just in the US.

These are the words of Neil Mehta, founder and Managing Partner of Greenoaks Capital, on the stage of Slush back in 2016. Greenoaks funds have delivered returns of 51 per cent annually since its founding in 2011.

European readers will be familiar with Greenoaks from their recent investments in Agicap, Vivid Money, not to mention Gorillas, Checkout.com and Deliveroo. Other notable investments outside the US include Coupang in South Korea, Flipkart and CRED in India, and Canva and Airwallex in Australia.

Clearly, a guiding principle through Greenoaks’ stellar decade of performance is its conviction that great companies are built on maxims that are universal. For the longest time the conventional wisdom has been that technology investors should be within driving distance of portfolio companies. That’s changing.

Internet Trends

We’ve previously discussed the backdrop of the meteoric growth in the venture market, but I recently stumbled onto an articulation that is worth sharing, from Semil Shah.

Investing in technology feels like the only game in town now in a pandemic world. Public investors are now full in privates; growth investors are doing As and Bs like they’re seeds; traditional VC firms are straddling seed and Series A (tho many have multi-stage arms); and seed investors, angels, rolling funds, syndicates, accelerators are conducting massive experimentation to unearth the next great thing.

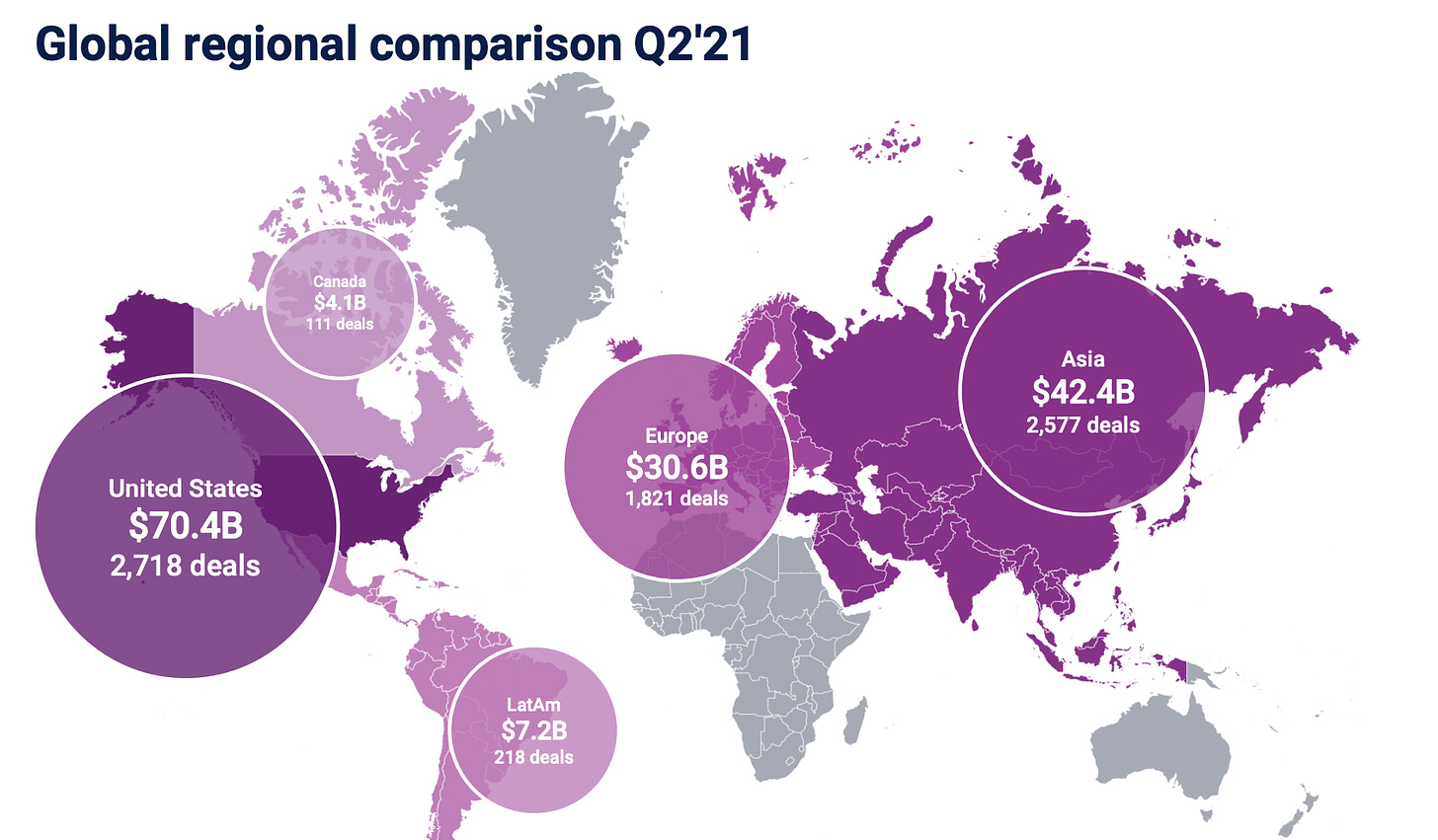

The US remains the centre of gravity for venture funding, of that there is no doubt.

That said, the factors that drove US hegemony of technology and innovation are worth studying from a deterministic lens. Let me borrow a mental model from historian Jared Diamond, author of the magisterial Guns, Germs and Steel.

History has gone very differently for peoples from different parts of the world. The last ice age ended 13,000 years ago. Since then, some parts of the world developed literate industrial societies with metal tools. Other parts developed only nonliterate farming societies. Still others had societies of hunter-gatherers with stone tools. Those historical inequalities still influence the modern world. They enabled the more advanced societies to conquer or exterminate the other ones.

When we examine the world as it is today, it’s tempting to attribute the status quo to proximate causes, i.e. the US developing the atomic bomb before Japan, which countries were the first to industrialise, and other such reasons. This is myopic. These proximate causes are simply outputs of ultimate causes, which explain why the US was the home to Robert Oppenheimer and the Manhattan Project and not Japan, or why the UK was one of the first to develop the steam engine. As Jared Diamond would argue, a multitude of reasons - ranging from political to environmental - combusted to deliver these outcomes,

Viewed through this prism, we can begin to appreciate why the same forces that brought the US to its perch at the top of the global innovation economy are now spurring value creation across the world. The same forces that helped Don Valentine build Sequoia into the world’s premier venture capital firm have helped Neil Shen become the world’s best venture capitalist as Managing Partner of Sequoia China.

Mary Meeker realised this on her first trip to China in 2003.

I remember being in China, and thinking that America has lost its technology edge. America led the world with the mainframe computer, the minicomputer, the desktop computer and the desktop Internet. But I concluded that in mobile Internet, American can’t lead.

Small sidebar here, but as it happens, Mary Meeker was advised to pay more heed to Chinese companies by none other than Chase Coleman, founder of Tiger Global.

I was visiting with Chase Coleman at Tiger Global [a New York-based investment fund], and a couple of his colleagues, and they said Mary – this was 2003 – you have not spent a lot of time focused on the Chinese Internet companies. That was true, although we were involved with the Sina IPO. They said, these companies are going to start generating some positive cash flow, you should pay attention to them.

We’ve talked about Coatue before, but it’s worth underlining just how much of Tiger and Coatue’s early success can be traced to Asia.

Let’s return to Mary Meeker. After graduating from Cornell with an MBA in 1986, Mary joined Salomon Brothers (of Liar’s Poker fame) on their training program. It was only in 1991 that Mary arrived at Morgan Stanley, where she carved a reputation as one of the most highly regarded technology analysts on Wall Street. She would eventually become the bank’s global head of technology research and cover some of the most defining companies born in the immediate wake of the internet era.

My move to investing was delayed in part because I just loved what I was doing. It was great to be able to cover companies like Lotus, Ashton-Tate and Dell; and Microsoft, Compaq and Apple, back in the early days. And then I got to watch the Internet come along, and I covered America Online, and then focused on Netscape, and then Google. I lived through that whole arc of the evolution of technology.

Her most notable legacy is the landmark Internet Trends report. First published in 1995, the report soon became on the most widely anticipated research pieces in Silicon Valley. Meeker and her team at Morgan Stanley managed to thread the needle of presenting the long-term direction of megatrends as well as a microscopic analysis of key shifts in consumer behaviours, with a global scope from the start.

In 2010, the report highlighted the markets that represented the fastest growing markets for mobile internet and how the Japanese market was a canary in the coal mine for how fast mobile penetration can overtake desktop.

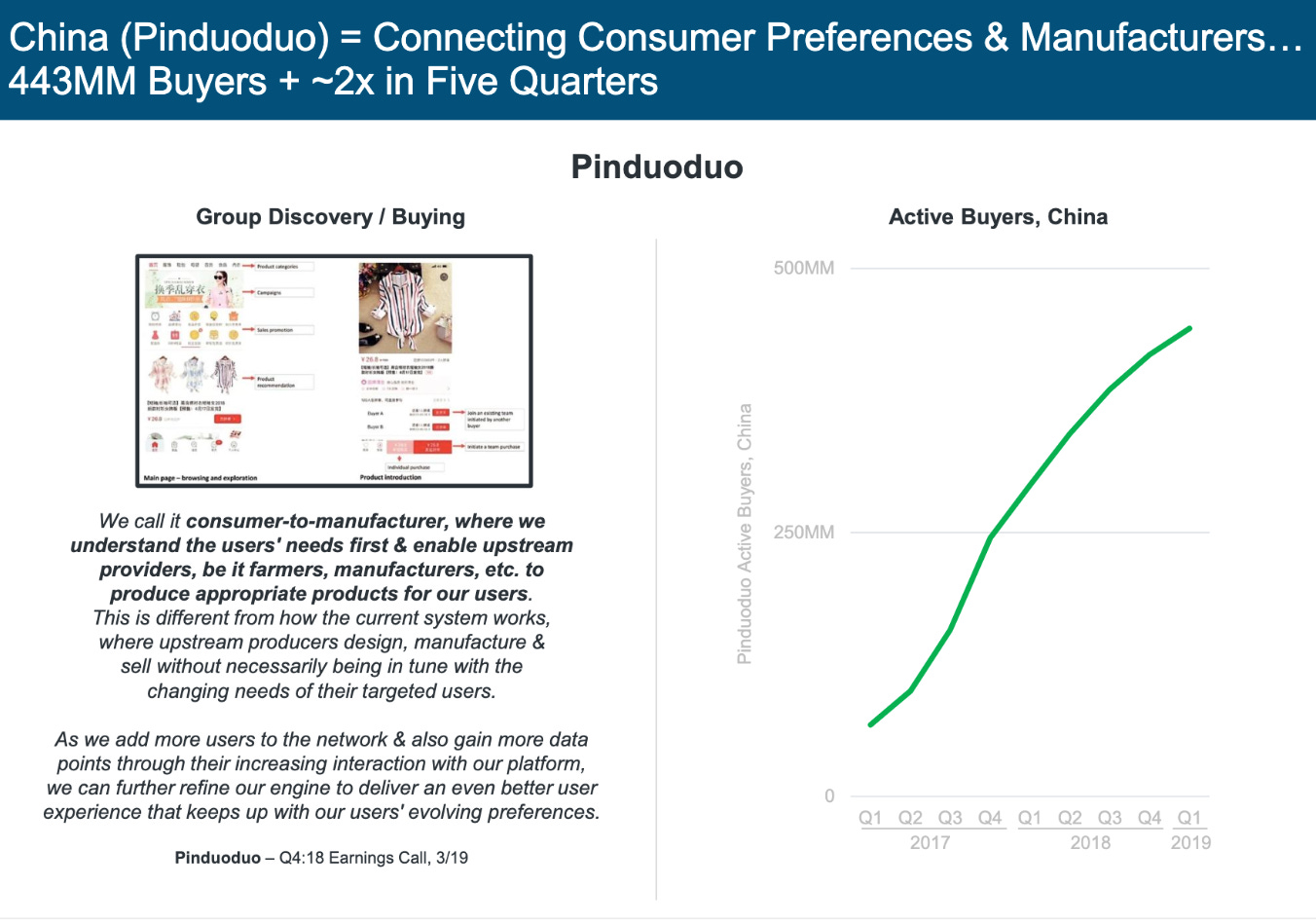

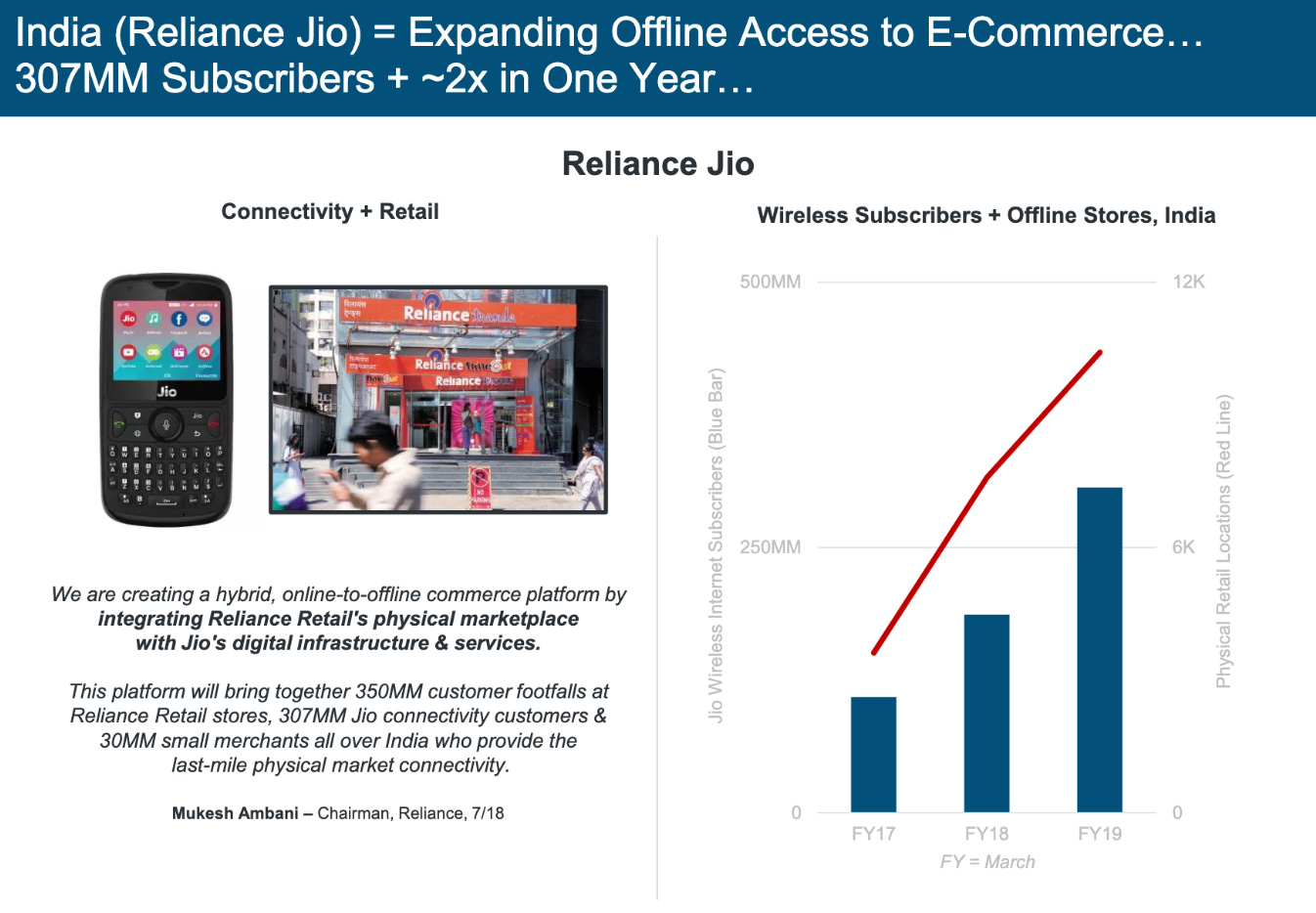

The latest report, published in 2019, has dozens of slides dedicated to markets outside the US, casting the spotlight on names that have now become familiar to even passive observers of Asian technology as well as those only known to astute observers.

Having covered the first arc of technology in the US at Morgan Stanley as a research analyst, Meeker began her investing career in 2010 at Kleiner Perkins. Over the next eight years she built out Kleiner’s growth practice, investing in the likes of Peloton, Pinterest, Airbnb, Instacart, Uber and Slack in the US, as well as Waze (Israel), JD.com (China), Trendyol (Turkey), and Spotify (Sweden) outside of the US.

In 2019 she left Kleiner Perkins to launch Bond Capital, raising a $1.25 billion debut growth-stage fund, one of the largest in VC history. This was followed by a second $2 billion fund in March 2021. Bond has already made over 40 investments and what’s immediately observable is that 25% are outside North America. It’s almost uncanny when you consider that this is exactly the non-US allocation she had at Kleiner.

Bond’s investments outside North America include investments in the Netherlands (Otrium), Germany (Flink), Australia (Canva), UK (Multiverse) and India (Byju). Bond’s pithy comment on the Byju funding rounding was characteristic of their research-driven modus operandi.

Endorsed by millions of students, Byju’s has emerged as a clear leader in education technology. We are excited to support a visionary like Byju and his team in their quest to continue to innovate and shape the future of education.

Let’s zoom out. Mary Meeker and Neil Mehta have both built hugely successful firms that have been global from the outset. Whilst this may be new to venture, hedge funds like Tiger, Coatue, D1, and Altimeter have always practiced this style of investing. To the extent that you can observe the indicators of a great market (as Andy Rachleff would put it), why would this be any more challenging in other geographies? Naturally there will be a learning curve to familiarise yourself with local nuances, but the difficulty of this is belied by the sheer number of firms deploying capital globally, often without local offices.

Other than the hedge funds, traditional US funds like Sequoia, Bessemer, Kleiner Perkins, CRV began investing globally many years ago. Insight Partners was second only to Tiger in H1 ‘21 on the leaderboard and are incredibly active in Europe without a local office. European funds that have begun investing outside the continent include LocalGlobe, Speedinvest and Target Global, as well as my firm Augmentum, where we focus on European fintech but have scope to invest a portion further afield, e.g. investing in DeFi fund ParaFi in the US.

Perhaps the very best example out of Europe is Hummingbird, who have invested in Europe, India, Southeast Asia, LatAm, Turkey and the US. Firat Ileri, Hummingbird’s new Managing Partner, described the rationale as:

We used to be a boutique fund, but we have the ambition to be more and especially to look for founders who have an independent mind and huge ambitions. To be able to find more companies we’ve gone more global, in order to have a better chance of finding these special stories.

Globalisation is irreversible, as much as the politics of recent years would have you think otherwise. Information, capital, and labour flow freely between states. The conditions that gave rise to American tech giants and the subsequent waves of innovation that followed have permeated all sectors of society, including financial services, healthcare, education and more. The blossoming of the internet, mobile and soon crypto across different markets will spawn trillions of dollars in value creation.

Preparing for success

As I was reading into Neil Mehta and Greenoaks, I realised just how much founders’ description of him resembled that of another legendary investor, Lee Fixel. Lee Fixel is of course the founder of Addition, another global investor straddling both early and growth-stage investing. At the time of writing, Addition is already working on a third fund, having raised two funds of $1.28 billion each since October 2020.

Fixel keeps a low profile, but his reputation precedes him from his days at Tiger Global, where he led several of the firm’s most lucrative deals, particularly in India. Whilst there’s no recorded interview with him, Forbes constructed a vivid picture of how Fixel stood out during his time at Tiger.

Fixel is known for chasing deals himself, from India — where he backed Flipkart, acquired by Walmart, and unicorn Freshworks, among others — to Columbus, Ohio, where he showed up to pitch Root Insurance CEO Alex Timm on a deal. A signature of Fixel’s startup courtship: lots of upfront research, like with Freshworks, where CEO Girish Mathrubootham says Fixel showed up in Chennai for a meeting, then surveyed his first 200 customers and provided the findings back to the startup. In Peloton’s case, Fixel sniffed around a retail location in Long Island pretending to be an interested shopper.

Glenn Kelman, CEO of publicly-listed real estate site Redfin, remembers Fixel showing up in Seattle for the afternoon with a duffel bag stuffed with papers, Fixel’s own research and diligence on Redfin, prior to a first meeting. “He said, I interviewed your customers, your employees, your ex-employees, your competitors. And we want to talk about why margins in San Diego in Q3 of last year were off.”

Compare this to how founders described Neil Mehta, per the Financial Times:

Some start-up founders who have worked with Greenoaks said they had not heard about the firm until they were introduced through a mutual connection, but Mehta arrived with volumes of research on the company and its competitors.

Before making its first investment in Deliveroo in 2015, Greenoaks analysed the company’s economics down to the level of individual neighbourhoods, said one person familiar with the process.

Carlos Garcia, chief executive of the Mexican used car marketplace Kavak, said Mehta ended an introductory call by asking if he could visit the company’s headquarters near Mexico City the next day. Mehta flew down and spent two days inspecting Kavak’s business.

This isn’t a top-down, index approach. This is almost atomic level of due diligence. The hunger to win is perhaps even more impressive.

As the world reopens, it’s becoming much more common for investors to fly out to meet founders in person, wherever that may be. Few arrive as prepared as Mehta and Fixel for success.