Hey friends! I’m Akash, partnering with founders at the earliest stages at Earlybird Venture Capital.

Software Synthesis is where I connect the dots on software and company building strategy. You can reach me at akash@earlybird.com if we can work together.

Current subscribers: 4,815

A few weeks ago I had the chance to have a deep dive into design partnerships with James Allgrove. This interview is full of actionable advice for founders of early stage B2B SaaS companies navigating their way through their first design partners.

This interview will soon be followed by a second part, shedding light on another key challenge for early stage founders - stay tuned!

James is an experienced operator and advisor of Seed to Series B companies. He works closely with founders of B2B companies on their go to market strategy, helping them to navigate key decisions like finding product market fit, transitioning away from founder-led sales and scaling their commercial functions. He was previously Chief Revenue Officer at FIdel API and prior to that spent 6.5 years at Stripe setting up their UK business and then New York office. His earlier career was in consulting at Bain & Company.

Design Partners

Let’s start by defining what design partners are and when you might use them?

Design partners are customers that you work with early on in developing a product or market. They help you to build out a product as well as your articulation of how a product can solve problems that your future customers have. I've seen design partners being used successfully at a few different points in the startup journey.

The first is right at the beginning when you have an idea that you have developed and validated by speaking with some potential customers. Now you need to actually build a product to start to solve whatever problem you've identified. At that point, it can be a good time to bring in design partners. What you're looking for is a company that has the pain point that you're looking to address with your product and is interested in working with you to co-create and to give you feedback as you build the product. At this point, you probably only want to work with a small number and so you can work very closely with them.

There are also opportunities later on in the startup journey, once you have a product, you might use design partners to expand in a certain direction or expand to a different ICP, different size of customer, or a new industry. It can also be beneficial if you're expanding internationally to work closely with one particular existing customer or early user in the new market in order to validate the product market fit in that market, and use them to develop whatever localized features you need.

Often founders will have to weigh up different characteristics of potential design partners, such as the urgency for that prospect, how representative that company would be of the wider ICP, the capacity that that stakeholder or champion may have, just to name a few. How do you advise founders to stack rank these different traits?

It depends slightly on what you're using the design partner for. Let's focus on that first bucket of you're building a product for the first time. At this stage you are looking for a design partner who can provide you with the precise input to build your product, hopefully helping you solve for the “product” part of product-market-fit. Therefore, you should optimise for a design partner that has a strong pain point in the area you are working in. If you identify a design partner with a strong enough pain the rest will follow – they will have sufficient urgency, they will create capacity to work with you to solve the problem and you will be informed as to which other potential customers are representative of this pain.

Champions

As you then think about the seniority to hone in on at the design partner for that cadence of feedback, how do you typically advise companies to navigate that?

For a design partner relationship to be successful, you’ll need to work with people who have a range of seniority including a champion/sponsor of the project as well as less senior folks who can provide the detailed feedback you need for a successful partnership. You usually need to start with finding the right champion as in most organisations, the more junior members of the team won’t feel empowered to work closely with you unless there is a push from above.

Pricing and contracting

A lot of companies hope to convert these design partnerships into eventual paying customers. What are the best practices for setting that up at the outset? How do you typically see that working best?

If you don't have a product yet, you can't really charge them anything, and you shouldn't waste your time trying to negotiate what they might pay in the future because you haven't proven any value yet. So if you're using a design partner to build your product for the first time, you need to be wary of the fact that they are doing you a favour and therefore, it's difficult to charge them.

That said, don’t miss the opportunity to test pricing during the design partner process. Typically, this would happen towards the end of the process where you would put your pricing structure with sticker prices in front of them and ask them to provide you input on the pricing structure, levels and alignment with the value they are getting from the product. You can caveat this by telling them this is not the price that they will pay, simply what you’re thinking of charging future customers. From this, you should try to negotiate a discounted price for your product after the design partner process concludes.

If you're in some of those later stage situations like using design partners to expand into new markets or ICPs, then you'll have established pricing. You can try and charge that or anchor them on a particular price, but then discount it, acknowledging that they're going to be giving you a lot of feedback and hopefully other benefits, like a case study, using their logo, etc.

We see more and more discussion around the formality of a design partner agreement or things you'd like to stipulate already upfront in a written document. What do you advise companies to think about here?

Just like with pricing, I have a preference for keeping things light here as you don’t want to slow things down or diminish the enthusiasm that your design partners hopefully have. Don’t wing it completely though! You should have some sort of agreement, even if this is just written out in an email and not a legal document, the point of which is to set and align expectations for both sides and avoid any future issues. Accordingly, it should cover how long the design process will be, what time commitment is required by each party, what each party is expected to do and not to do and getting in return. You can also use it to set a date to discuss whether they will convert to a paying customer.

Setting a timeframe is important because you want to create urgency and have a clear check in dates along the way. You may find that they're a good design partner, but they're not the right type of customer for what you actually are building once you get into the process with them. Therefore, you also need to have some options to get out, just like they will.

Design Partner <> ICP Fit

As you outline there are these stages to a design partnership with the timeline that comes with. As companies refine their ICP in that journey, they may discover that of the dozen or so design partners they're working with, some no longer fit that ideal ICP. How frequently should companies have gates like that to assess if design partners still fall into that ICP or not?

In the beginning, if you're building a product from scratch, you have to be very open minded about where the product goes because you're really focusing on solving a particular pain point, and you should have selected your design partner accordingly. If you've selected the right kind of design partner for the pain that you are looking to solve, then it’s likely that company will become part of your ICP. So at this stage, it is difficult to discern the design partner from the ICP itself. If you're later on and you're using design partners to build new features, for example, you might have multiple design partners, and there might be a more narrow type of engagement with them.

In that case, if you don't feel like you're making good traction with a particular design partner, particular feature, then it's fine to say, ‘it doesn't feel like we're able to solve this problem’ or ‘this is interesting but it’s going in a direction that isn’t valuable for us’. Having multiple design partners in that situation can work well because it means you don't have to go back to step one and find a new one to start working with.

Discounting

As you mentioned, pricing should come later in the journey, but there should be discounts given that they're giving feedback and potentially case studies. Do you have estimates that you tell founders to think about in terms of how much they should discount?

I don’t think that there’s a standard answer here – this will come down to how much of a product you are bringing them to start with and how much work will be required from their side. It will also depend on what else you’re getting from them in return – things like logo usage, case studies, co-marketing or reference calls with your next set of prospects. As your product develops and provides more value you should be able to consistently charge more and the inability to often indicates you have more work to do on the product side.

Ultimately, it's a bit of a judgement call. You should be optimising to keep them as a customer, unless they really don't want to be. I've seen everything from 20% to 80% discounts on the proposed sticker price. Maybe 40% to 50% off is about right? But it's hard to say, it totally depends on the situation.

Moving Upmarket

You alluded to how companies can use design partners for a new ICP. For example, an SME vendor is starting to build for the enterprise; do you see value in having design partnerships for that new segment whilst in parallel maintaining the R&D and S&M spend/allocation on the core product? Is it sensible to have those two in parallel?

Firstly, think carefully before you do shift your focus to a new ICP, especially if it’s to enterprise companies. Don’t do it just because a large company comes along offering to be a design partner. It should be a very conscious choice that you make and well considered, because it is a big thing to do and can be a huge distraction.

That said, if it is the right choice for you, then I think that this can be a good way to move upmarket. For example, you could take the type of customer and use case that you already have in the mid-market and then find the enterprise equivalents of those companies. Once identified, you can attempt to secure them as design partners and build out the ‘enterprise’ features you need to win subsequent large customers.

One watch out here is to make sure that this doesn’t distract your existing team from your current ICP and core customers. Ideally you would use separate resources to secure and work with these design partners, this is often the founders job, leaving the existing sales team to continue to bring in revenue from your ICP.

This approach has two benefits. Firstly, it reduces the distraction in the rest of the company. Secondly, you concentrate all of the learnings and the feedback on a small number of people, which means you can iterate faster. This tends to be a good way to set things up to ensure you’re getting as much as possible from the design partnership as possible.

Where I've seen this go wrong is when a company decides to move upmarket either because a big customer has approached them or they want to because they think there's a lot of revenue upside in doing so, and then the whole company gets refocused on that and they neglect their core customer. Building an enterprise sales motion and a product can take a long time.

So you risk ending up in a situation where you've neglected your core business, you haven't successfully got traction in enterprise, and then you end up getting into a very difficult situation where the company's not growing anymore, everyone's distracted, nobody knows what priorities are, and it can all unravel very quickly from there.

Cultivating alignment

You've already spoken to this in the first answer around the acuity of the pain point really dictating the other criteria for design partner selection. Are there tactics that companies can use to help make design partners feel even more invested in the success of the design partnership from the beginning and then as you go through it?

The most important thing is having them feel the pain very, very acutely. If you have that, everything else tends to come quite naturally.

There are certain things I've seen that can work well. Giving the design partner the option to invest in the company, or having them invest upfront, can be an interesting way to kind of keep them involved long term and to align incentives. The trouble with that is you don't want to create a situation where you're just building a product for them and then they get annoyed if you start selling it to their competitors. So you have to be wary of that dynamic. Secondly, you don't want them to have too much control over your roadmap in the long run because you might decide actually they're nothing like your ICP. If they feel like they have a lot of influence over you because they've invested, then that can create a difficult situation. I've seen that done to positive effect and to negative effect as well.

The other that I've seen that's a little bit easier and a little bit more flexible is also your champion, being a bit more involved in the long run in the startup. So maybe as an advisor or you can give them a board seat for the first year or two that can also bring in that person in a bit more of a flexible, time limited way. Then if you want to move over to a different ICP or you need that board seat back, that's easier to do and you can set that expectation up front. Likewise, you can set up an advisory agreement for just a year and then see how it goes and if that person continues to be useful, you can renew it. So there's also the kind of next level down of keeping people involved and brought in, but without locking yourself in too much.

Charts of the week

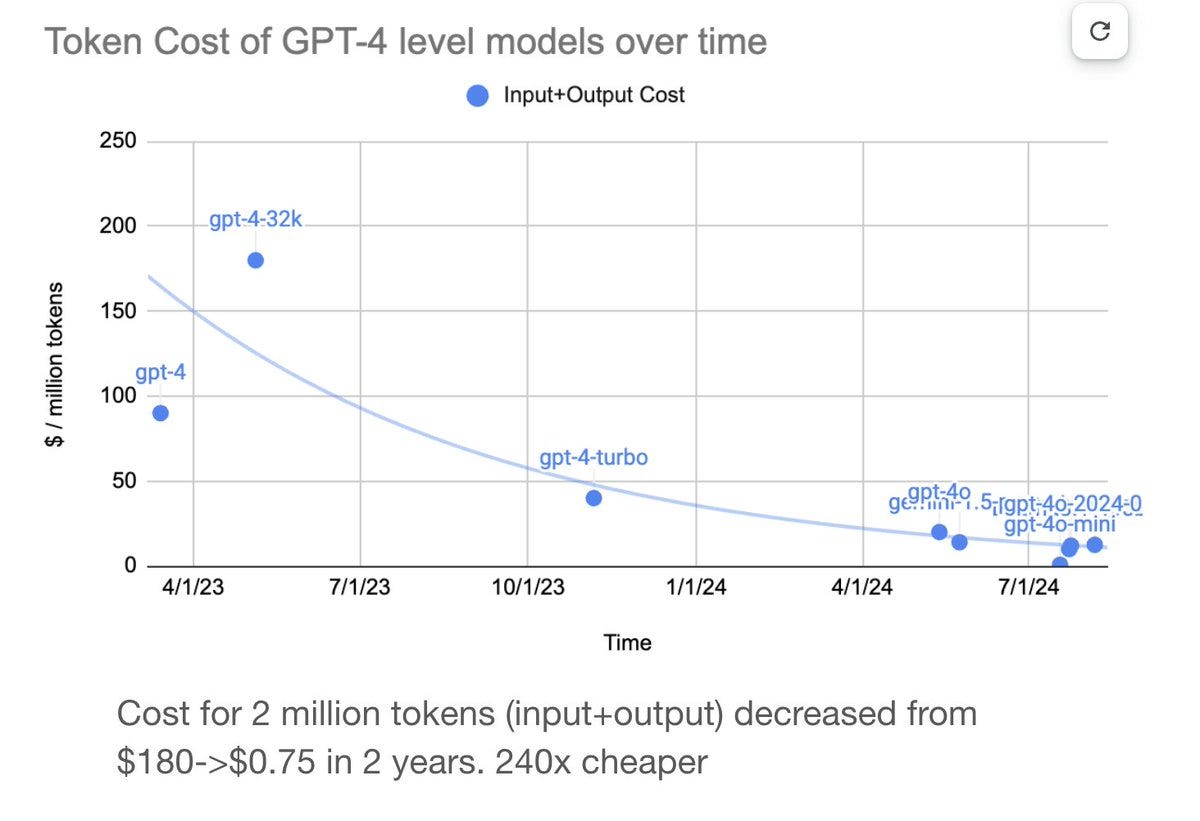

The rapid deflation of token generation is going to have several second order effects that are still hard to imagine: cost of 1M tokens has dropped 240x in ~18 months

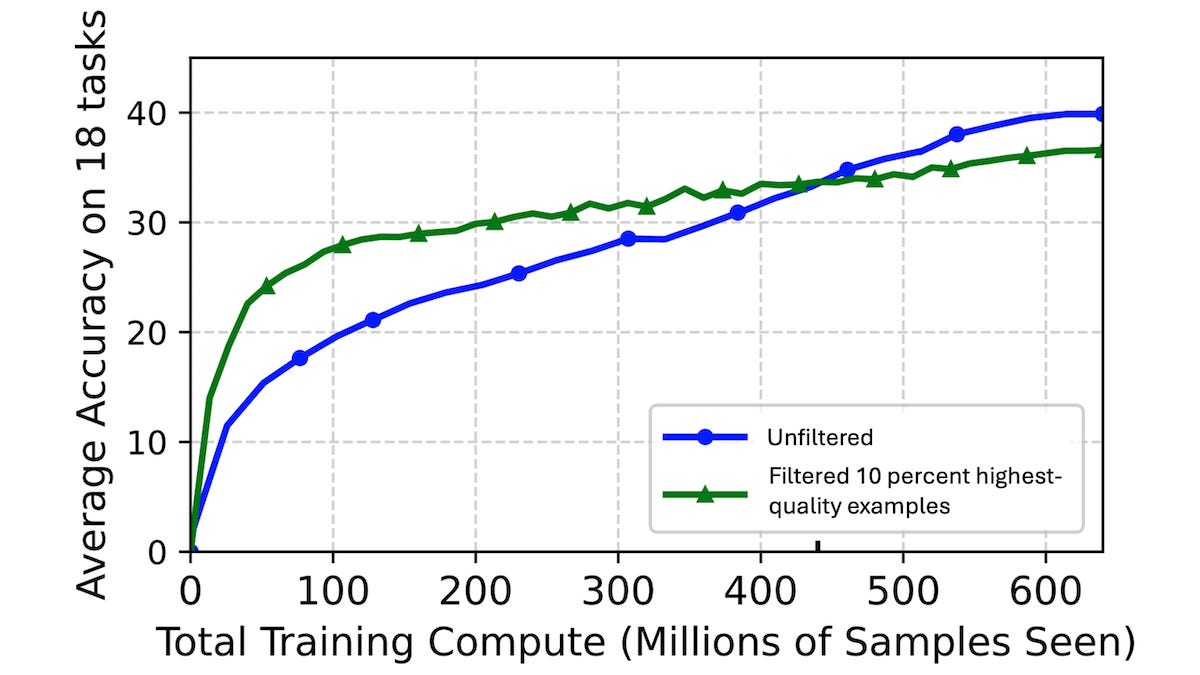

New research on scaling laws for data quality suggest multiple training runs on the same higher quality has diminishing returns relative to adding lower quality data to the training dataset

Curated Content

The Man Behind Silicon Valley’s Favourite Blog by David Perell

Chip War's Chris Miller on Putin, China, and The Future by

What I learned at Palantir — Hire spiky pioneers by Robert Fink

The big stack game of LLM poker by Sarah Tavel

Speed Above All Else by Alfred Lin

Quote of the week

‘I’ve spent a lot of time over the past decade studying great entrepreneurs and geopolitical competition. Fundamentally, neither founders nor countries think like economists. Great founders may have shareholders who would like them to consider return on equity, but that’s not how they make decisions. Think of Jensen Huang ten years ago – even though Wall Street was warning him against it, he still poured Nvidia’s money into building out CUDA and the ecosystem around it. If your mode of thinking is purely economic – focused on return on equity or maximizing shareholder value – you miss a lot of what actually drives competitive, successful people.’

Thank you for reading. If you liked it, share it with your friends, colleagues, and anyone that wants to get smarter on startup strategy. Subscribe below and find me on LinkedIn or Twitter.