👋 Hey friends!

I’m Akash and welcome to Missives, where I write about software, fintech and go-to-market strategy. You can reach me at akash@earlybird.com.

Thank you for reading! If you enjoy these Missives, please share them with your friends and colleagues 🙏🏽. Have a great week!

Current subscribers: 2,915, +40 since last week

A sea change is underway.

‘And importantly, if you grant that the environment is and may continue to be very different from what it was over the last 13 years – and most of the last 40 years – it should follow that the investment strategies that worked best over those periods may not be the ones that outperform in the years ahead.’ Howard Marks

Years of low rates funnelled institutional capital towards higher risk strategies and increased allocation to alternative asset classes, including private equity and venture capital.

A new ‘normal’ of 2-4% base rates is ominous for precisely these allocations.

Lastly, there is a forecast I’m confident of: Interest rates aren’t about to decline by another 2,000 basis points from here.

In this setting, not only does venture look less attractive as an asset class compared to low-risk money-market instruments, but also against passive large-cap tech exposure.

Power laws are ubiquitous. In people, in startups, and certainly in venture capital.

Top decile fund managers that consistently outperform over multiple vintages are exceptionally rare.

The dispersion is stark. As a matter of fact, simply allocating to public, liquid Big Tech equities would have outperformed top quartile managers over the last two decades. The case for the median manager is even more jarring.

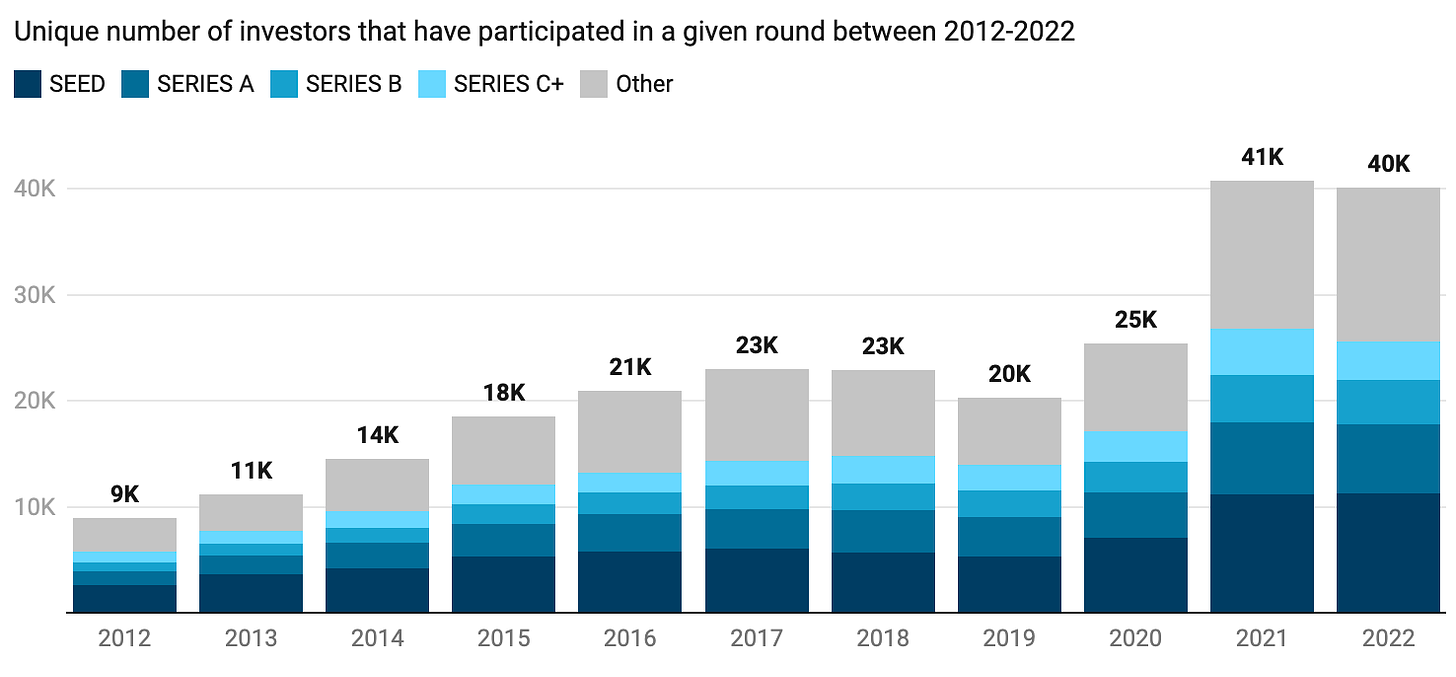

The preceding ZIRP era enabled the swelling of venture to unsustainable levels; the number of funds grew 4x between 2012 and 2022.

This in turn creates the wrong incentives to found a company.

‘Meanwhile, the supply of startup equity remains constrained. Rather than potential founders becoming more eager to start companies for "fundamental" reasons, entrepreneurs are reacting to investor sentiment. While there's been some growth in supply at the earliest stages, the fundamentals haven't necessarily improved much, which is why late stage deal flow hasn't grown any faster than U.S. GDP.’ Nnamdi Iregbulem

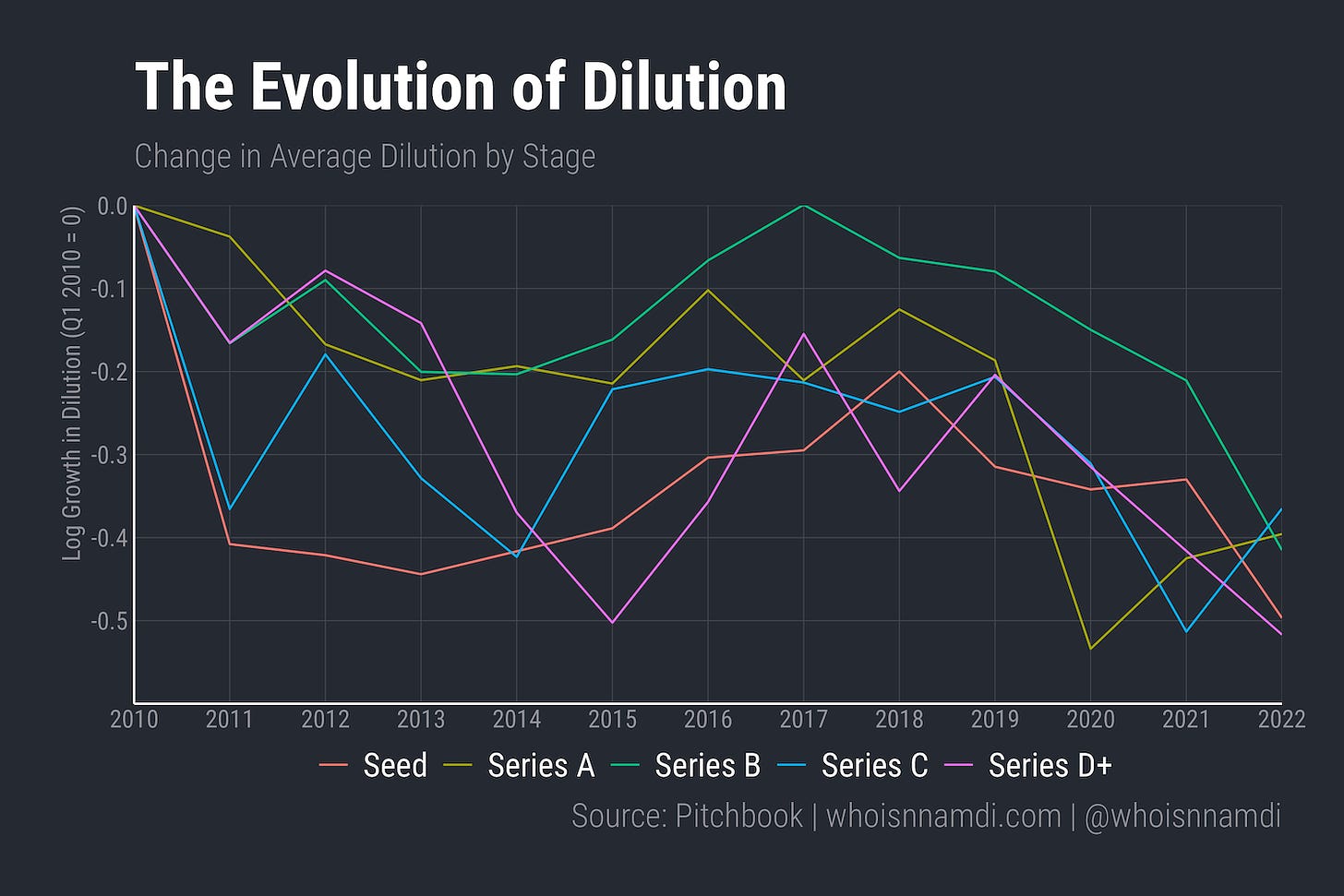

The demand for startups far outstripped supply. Ergo, capital became cheaper and dilution fell at every stage.

Disentangling the drivers of increased rates of new business formation is difficult, but it’s clear that abundant dry powder in venture played some role in the proselytising of would-be founders.

If capital is to recede from venture, founders operating today would be well within their right to rationalise raising more capital by pointing to category saturation. Competitors are well capitalised and the average startup has 5x more capital available today than their counterpart in 2013. Do companies need 5x more capital than ten years ago?

Here it’s important to apply ‘second-level thinking’:

Second-level thinkers understand that the convictions of the masses shape the market, but if those convictions are based on emotion instead of sober analysis, they should often be bet against, not backed.

But the person who applies logic and insight, rather than superficial views and emotion, sees something very different.

Other than salaries, other costs of running startups have been modestly increased, and salaries (or founders’ living expenses) certainly haven’t increased 5x. The distortion of sales compensation is also clearer and clearer in an environment of lower growth and less capital to subsidise wage inflation.

This gets to the heart of an immutable virtue, constraints. Capital may or may not abate, but the merits of constraints are independent of the cost of capital.

‘I believe that excess capital makes companies weak and unfocused.

I believe limited capital makes companies strong and focused.’

Fred Wilson

Faced with category saturation and longer sales cycles, founders would of course be wise to lengthen runways with more capital.

The intellectual honesty is about how much is enough to induce the right focus as a company.

Silicon Valley lore is chock-full of examples of capital constrained larvae that metamorphosed into generational companies.

This is Tony Xu, co-founder and CEO of Doordash, describing the importance of constraints to Patrick O’Shaughnessy:

And one of the things that really helped with this was a constraint, which was our budget. We had very little money in the early days. DoorDash struggled to raise a seed round when we got started, so we had very constrained wallets. And as a result, I think we started noticing that something seems to be working because our bank accounts are not going down, even though we have a very small bank account.

Part of that, I just say this tongue-in-cheek, but was this maniacal focus on always making sure that our unit economics for orders worked. In fact, when I looked back over the 7.5 years that we've been building DoorDash, it was critical to do that because in the first 5-5.5 years of the company's life, we were very undercapitalized compared to any of our peers. Maybe 1/100 of some of our peers. And that capital efficiency I think started, yes, because of the constrained budget.

Brian Chesky and his fellow Airbnb cofounders were rejected by every investor they met. Desperation led to Chesky racking up $30k of credit card debt to stay afloat, but this wasn’t enough.

The constraint forced creativity. Chesky and his cofounders launched cereal boxes themed after the 2008 Presidential election, pitching each box as part of a limited edition collector item to mark up the price to $40 for what would ordinarily be a $4 box of cereal.

Later, Paul Graham would recite this ingenuity and perseverance as the most important evidence of the traits that secured them YC investment (Sequoia Capital would go on to lead their next round post-YC).

Though the Airbnbs only did ok in the idea department, they did spectacularly well in this department. The story of how they'd funded themselves by making Obama- and McCain-themed breakfast cereal was the single most important factor in our decision to fund them. They didn't realize it at the time, but what seemed to them an irrelevant story was in fact fabulously good evidence of their qualities as founders. It showed they were resourceful and determined, and could work together.

In a separate essay, Paul Graham describes how Airbnb carried forward the principle of constraints well after funding was readily available:

Airbnb waited 4 months after raising money at the end of Y Combinator before they hired their first employee. In the meantime the founders were terribly overworked. But they were overworked evolving Airbnb into the astonishingly successful organism it is now.

Today, ZoomInfo is one of the most capital efficient software businesses we’ve ever seen, boasting FCF margins of 34%, gross margins of 84%, and a Rule of 40 of 72%. This world-class profitability and efficiency can be traced back to founder and CEO Henry Schuck’s constrained beginnings.

Like Brian, Henry had to take out $25k of credit card debt, adding to $150k of college debt, to get ZoomInfo (then called DiscoverOrg) off the ground. Being based in Columbus, Ohio didn’t help with fundraising, of course.

‘And we just invested all of the money that we made in the company back into the business. And the business grew profitably, obviously because we have no other money. So there was no other way to build the business other than to build a profitably. And it grew fast in the space.’ Henry Schuck

By the time the business took in outside capital for the first time in 2014 from TA Associates, the company had $35m in revenue, growing 60% YoY, with 50% (!) EBITDA margins. The focus on efficient, profitable growth from the very beginning made ZoomInfo an n-of-1 software business that was able to finance the subsequent acquisitions of RainKing and ZoomInfo through debt.

‘Fast forward 10 years, and we had the opportunity to acquire them. And why did we have the opportunity to acquire them -- it wasn't just because at that point, we had built a bigger business. At this point, we were $80 million business and they were a $40 million business.

But it was because we were operating that business so much more efficiently than they were. So we had all this room actually to raise debt to do the acquisition. So we didn't have to dilute any of our shareholders, and we also didn't have to go raise more money from our private equity sponsors to be able to make this acquisition.’ Henry Schuck

Toast’s cofounders struggled to raise capital despite being three of the best engineers at a company Oracle had acquired for $1bn, Endeca. Endeca’s founder, Steve Papa, ended up investing $500k personally in 2013 after every VC he introduced the founders to ended up passing. Still, the mission to replace incumbent POS systems was daunting and $500k didn’t seem like an awful lot to take on incumbents Micros and NCR. As Kent Bennett, then Associate and now Partner at Bessemer, put it:

I felt like screaming. “The three of you are going to build a system to replace a forty-year old software stack with thousands of required features? A system that needs to work every minute of every day or else risk putting a restaurant out of business???”

Kent passed when Steve first tipped Bessemer off.

Then, constraint forced creativity.

I thought it would take them years to build a working POS. They did it in months. Leveraging Android, hidden in Apple’s shadow at that time, was a stroke of genius that opened up a variety of cheaper hardware options and gave Toast control over the operating system.

Bessemer would go on to lead the Series A in 2015 and the rest is history; today, Toast is at $1.1bn in ARR and is one of the best examples of vertical SaaS scaling with fintech products.

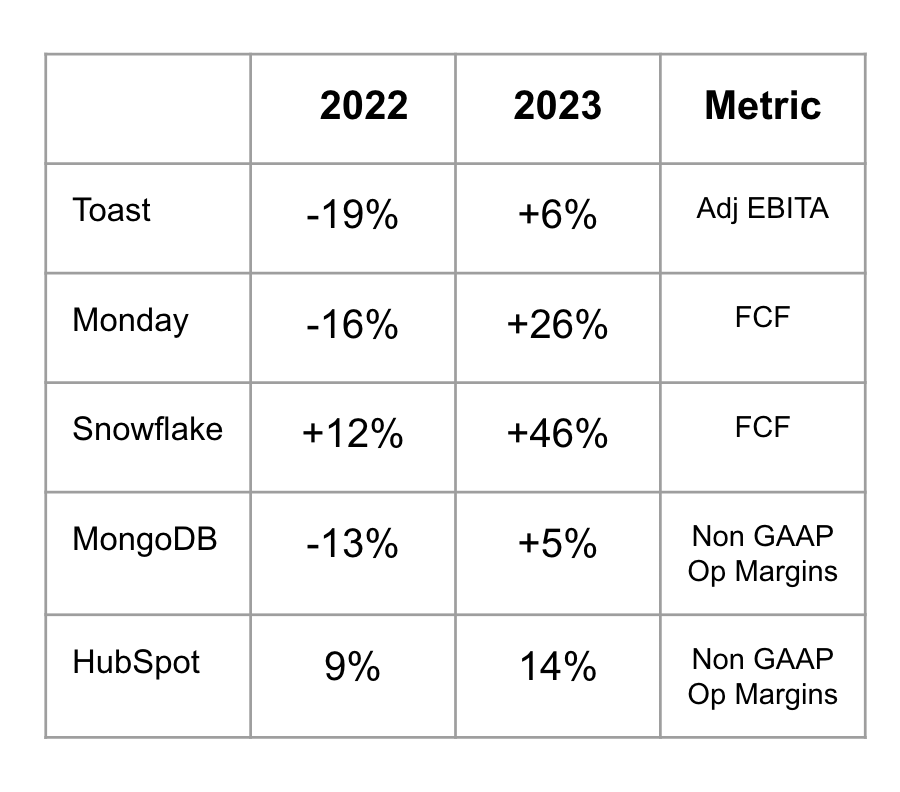

The speed at which mature software companies have been able to recalibrate towards efficiency in the new normal is remarkable, and provides ample evidence of the viable path to efficiency.

Knowing that talent is the majority of a startup’s costs, we have to honestly grapple with managerial diseconomies of scale:

‘And that's like a sort of Fermi Paradox Great Filter. It wipes up an amazing amount of startups. And the way that's done is a collapse in the labor productivity per person. There's a term in micro economics called managerial diseconomies of scale.

And I think in some ways the angle of the decline of productivity per person is the difference between the sort of the Stripes, the great startups, and the failures. And maybe if you're a great startup, as you go from 10 people to 100 people output per person drops 15%. And if you're a bad startup, it actually drops over 90% with the result that often 100-person startups produce the less than they did when they had 10 people, because the managerial collapse has been so extreme.’ Charlie Songhurst

Terrence Rohan wrote an excellent rallying call for companies to build more and raise less, pointing to an emerging cohort of companies trying to straddle the growth demands of venture with the efficiency that begets durable value creation.

They are seeking to combine the growth of targeted venture funding with the durability found in bootstrapping (i.e. profitability).

Their goal is to build a viable business first, while also harnessing the growth, network, and brand benefits of strategically raising capital from top investors.

This isn’t a call to raise less capital. Far from it. Klaviyo, the first major software IPO candidate in nearly 2 years, raised $454.8m in primary capital since inception, of which they have spent only $15m and achieved FCF margins of 8% and rule of 40 of 65%; efficiency that’s emblematic of previous companies to open IPO windows.

No, instead, this is a paean to the merits of constraints.

Another company that filed for IPO last week was Instacart, which has had it’s own journey of embracing constraints to eventually deliver $242m in earnings in H1 ‘23.

As Ravi Gupta, then CFO of Instacart and now Partner at Sequoia Capital, told Patrick O’Shaughnessy:

Our last valuation was $2 billion. We had been named, either Forbes or Fortunes, number one most promising startup in 2015. To the outside world, we were crushing. And honestly, to a lot of the team inside the building, we were crushing, when in fact, our unit economics, our business wasn't working. We were losing a lot of money on every order.

So the hardest time was then, of getting the whole company focused on, if we don't fix our union economics, we don't have a business anymore. That was incredibly, incredibly difficult, but it was hugely formative. It was the only reason that we survived was the company's insane focus on one thing.

For more writing on constraints that inspired this post, read Semil Shah, Fred Wilson, and Aashay Sanghvi.

🗞 Reading List

Why You (Probably) Don’t Need to Fine-tune an LLM

The end of incrementalism: how AI will reward maximalist start-ups

Hamilton + Burr = JPMorgan Chase

The Contrarian Strategy of OpenAI

Venture Capital — We’re Still Not Normal

The New Era of Efficient Growth

🗯️ Quotes of the week

‘Another advantage of bad times is that there's less competition. Technology trains leave the station at regular intervals. If everyone else is cowering in a corner, you may have a whole car to yourself.’ Paul Graham

‘People are really a power law, and the best ones can change everything. Betting on people who have these incredibly high ceilings and a reasonably high likelihood of getting there I think is much of where the game should be, even more than most.’ Sam Hinkie

Thank you for reading. If you liked it, share it with your friends, colleagues, and anyone that wants to get smarter on SaaS, Fintech and GTM. Subscribe below and find me on LinkedIn or Twitter.

Good strategy originates from having constraints and having to make hard choices. When many companies get too big they stop making hard choices - due to less constraints (on the surface).