A paean to fintech's resilience

Talent and capital will remain undeterred; we have lots of work ahead of us

Hey friends,

It’s been nearly a year since I last wrote anything. A lot has happened.

I’ve moved into early stage investing at Earlybird. I’ll continue to spend a lot of time in fintech and crypto, but I’ll also be training other muscles to become a generalist software investor over time. It’s highly likely that the topics I write about will reflect that.

In this break from writing, many readers reached out to encourage me to resume writing. Inexplicably, a few bits here and there managed to resonate with some of you. For that, I am eternally grateful.

Today I’m writing about a sector dear to me: fintech. I have a pipeline of ideas that will delve far deeper into specific fintech topics than today’s post, but I’m not going to make promises of cadences that I then slip up on after two posts. I’ll do my best :)

With that, let’s dive in!

“Mostly it is loss which teaches us about the worth of things.” Arthur Schopenhauer.Unfortunately for the Product Manager that joined a late-stage fintech before tech's reversion to the mean, this aphorism is registering the hard way.

In the last six months, the F-Prime Fintech Index is down 60% versus a 30% correction in Bessemer's Emerging Cloud basket of best-in-class cloud software companies.

Even Stripe, the canonical pride of fintech, cut its valuation by 28% (n.b. this was likely a proactive measure to look after employees). If that doesn't give enough pause, its listed peer Adyen has had a much rougher time of it in the public markets, despite near-parity in growth.

Much ink has been spilled dissecting the downturn we’re experiencing, but what's particularly striking is the high degree of correlation we're seeing between macro conditions and software multiples. As Morgan Stanley recently wrote:

'The normalization of multiples environment amidst tightening liquidity conditions is unprecedented relative to other financial crises, given the rising rates and inflationary environment (elevated overall correlation)'.

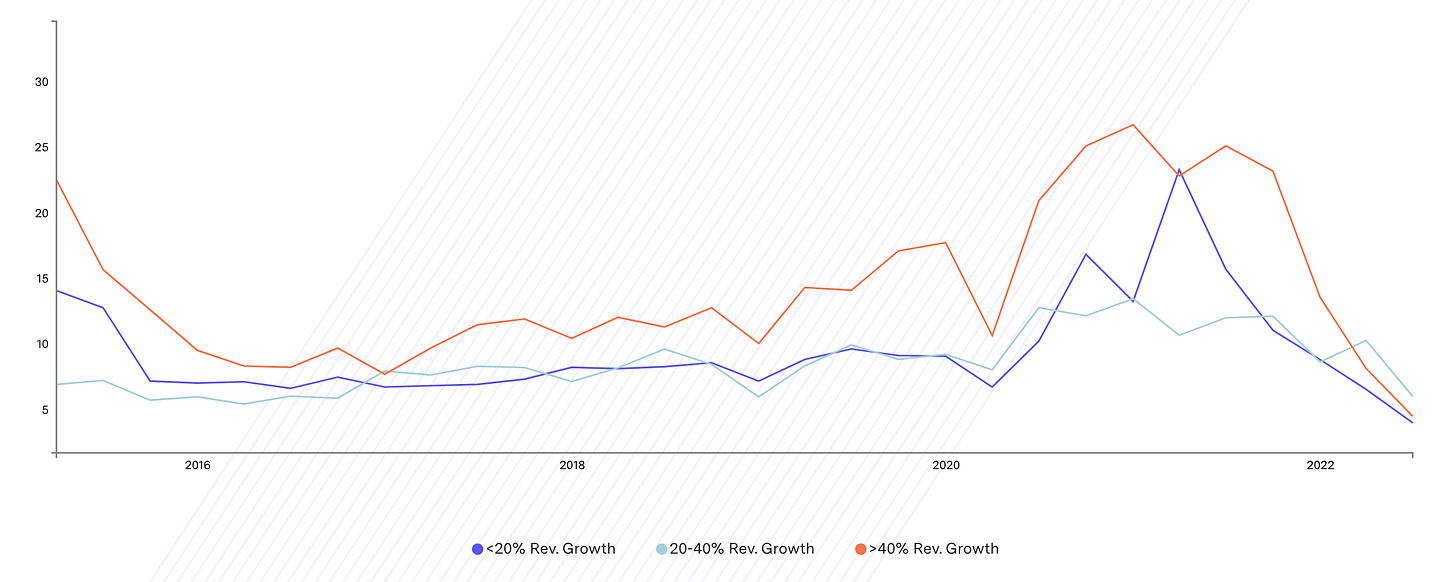

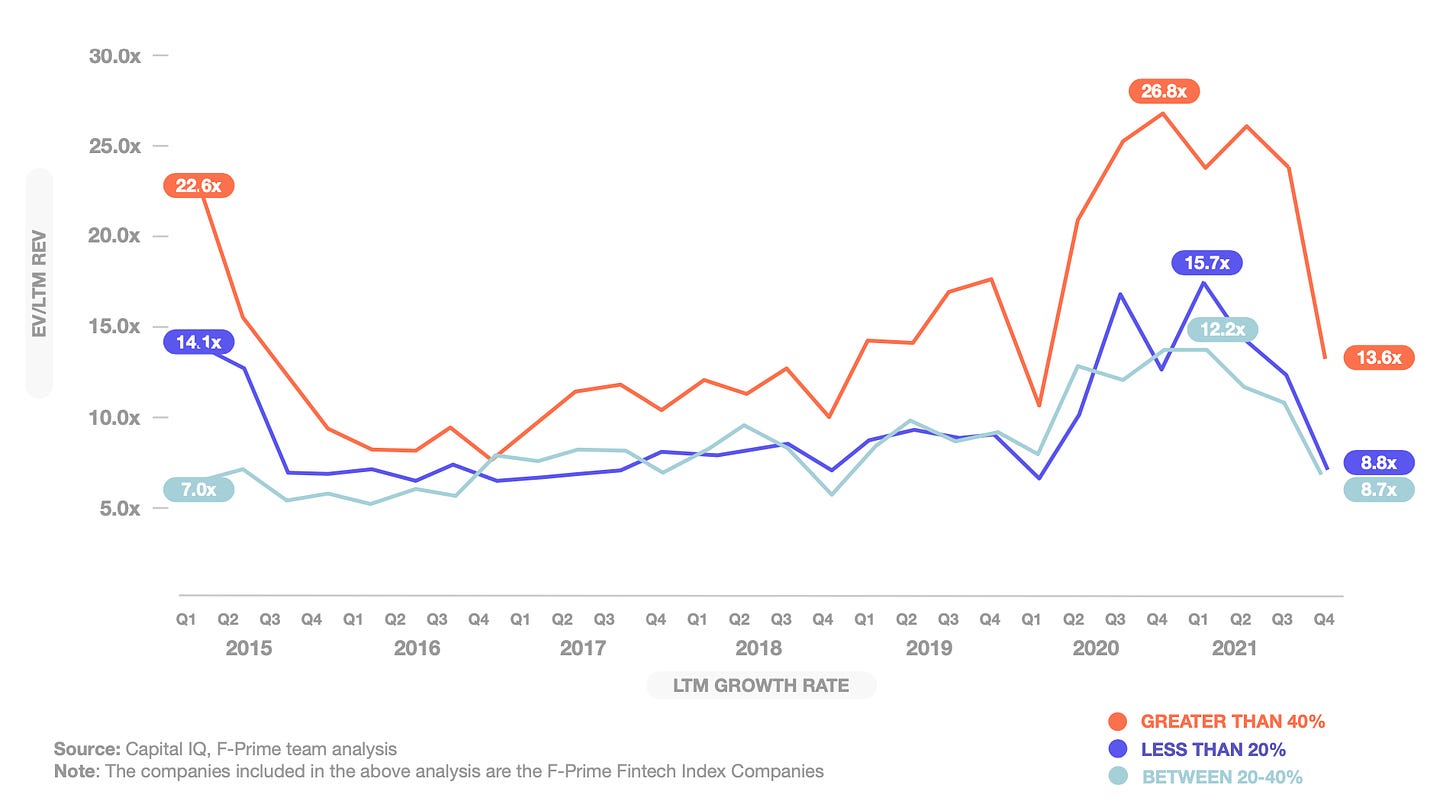

Multiples for SaaS businesses have come down to even below pre-Covid levels, with fintech multiples being no exception.

This vertigo-inducing fall in recent months is so hard to stomach precisely because the 2010s represented fintech's zenith, with many predicting an even brighter future for the 2020s. Renowned fintech and public markets analyst John Street Capital wrote in December 2019:

We’ve seen an explosion of all things “FinTech” over the past decade and we think this will only continue in the decade ahead.

The advent of ancillary technologies on mobile, the use of machine learning, and artificial intelligence, opened up the path for companies that weren’t feasible 10+ years ago and will lead to companies we cannot fathom today 10 years from now.

This was the same year Matt Harris of Bain Capital Ventures heralded the emergence of fintech as a platform of similar significance to the Internet, Cloud and Mobile.

The pandemic accelerated fintech adoption as incumbents proved too unwieldy to adapt to customer's needs in times of crisis. The early signs in the pandemic were that the principles of customer-centricity, which were native to fintechs, would triumph.

Add to this mix unprecedented levels of stimulus and loose monetary policy, with a healthy dollop of SPAC vehicles, and we had a two year feeding frenzy where the amount of dollars raised by venture funds skyrocketed, the cost of capital came down to zero, and retail investors surged into stock trading as a pastime. Listing conditions couldn’t be more fertile - it's no wonder that we saw 8 of the 10 largest fintech IPOs occurring in 2021. In the private markets, a fifth of every dollar invested in venture was into fintech. Contrast that with 2010, when fintechs represented 4.2% of transaction volume.

All of these elements combusted in 2021 to elevate public fintechs (those growing >40% YoY) to revenue multiples of 26.8x, compared to historical software multiples of 8x.

As we watch the correction unfold, it's worth taking a moment to reflect on the journey thus far, and the many grounds for optimism.

Redemption

The 2008 Great Financial Crisis (GFC) triggered an inquisition into the financial services industry's failings across the world. These inquests ended up having far-reaching consequences well beyond containing speculative practices such as proprietary trading (Inside Job, narrated by Matt Damon and analysing the crash, is as good as any popcorn thriller). Ultimately, the ensuing regulatory and legislative changes planted the seeds for a generation of ‘fintech’ companies to sprout that served those that were underserved by financial services incumbents.

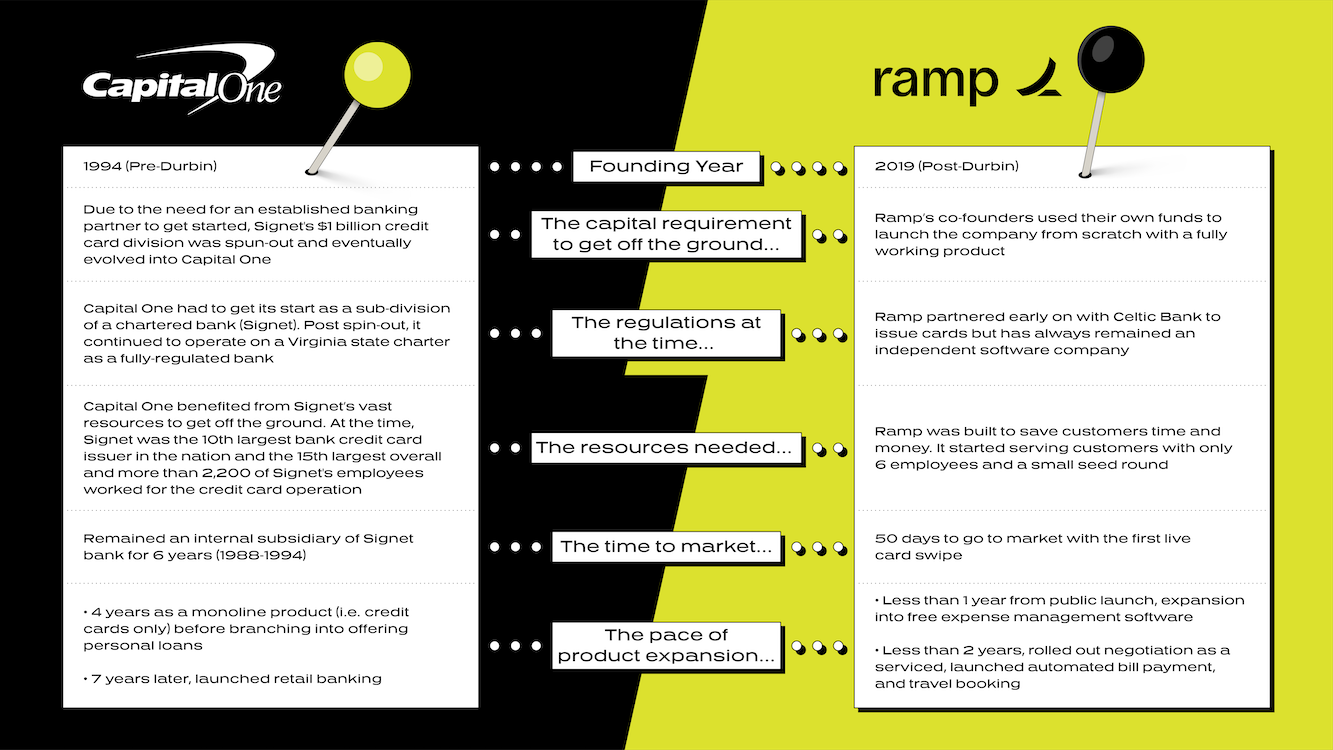

Eric Glyman, CEO of Ramp, laid out the evolution of fintech in the US by tracing it back to an amendment to the Dodd-Frank Act, and in particular an amendment by Illinois Senator Richard Durbin. Dodd-Frank was the primary piece of reformative legislation passed under the Obama administration in the wake of the GFC, and the Durbin Amendment granted the Federal Reserve the power to regulate interchange fees. The Dodd-Frank Act itself was reinstating the separation of investment activities from deposit-taking institutions, a crucial guardrail that protected consumers since the Glass-Steagall Act was signed after the Great Depression in 1933. Whether Dodd-Frank was ambitious enough is another debate, but the Durbin Amendment may well have had an equally profound impact.

The GFC ignited enough fires in the bellies of entrepreneurs intent on defining how technology could reinvent financial services, with many of these propositions starting out with consumer-facing products. The Durbin Amendment allowed banks with less than $10 billion in assets to charge higher interchange fees, a workaround that was particularly appealing to consumer fintechs seeking to monetise their customer bases. Take Glyman’s example of neobank Chime, which focused on serving lower income customers with fee-free banking (n.b. ~10-15m in the US remain unbanked, ~20-25m underbanked and overdraft 3x+/year).

In order to offer these accounts to customers, however, Chime had to integrate with license-carrying sponsor banks that were endowed with the ability to charge higher interchange by the Durbin Amendment. In essence, consumer fintechs function as quasi-distributors for these banks, collecting deposits for the banks to earn net interest on, whilst the fintechs collected the higher interchange.

As straightforward as that sounds, these fintechs faced challenges plugging into these sponsor banks.

Fintechs needed to build secure infrastructure that would allow their modern platforms to speak to bank back-end systems (many of which are still run on mainframes and rely on COBOL, a dying programming language popular in the 1960s), as well as meet compliance requirements. As a result, most early fintechs found themselves spending up to two years—and millions of dollars—just building connections into their partner banks’ legacy infrastructure.

Before we continue, let’s introduce the concept of the apps-infrastructure cycle. Dani Grant and Nick Grossman of USV described it as:

We are not in an infrastructure phase, but rather in another turn of the apps-infrastructure cycle. And in fact, the history of new technologies shows that apps beget infrastructure, not the other way around. It’s not that first we build all the infrastructure, and once we have the infrastructure we need, we begin to build apps. It’s exactly the opposite.

Chris Dixon and Fred Wilson discussed the concept as a mental model to use when thinking of web3, but an even longer arc that this applies to is the evolution of the internet.

Each time the apps => infrastructure cycle repeats, new apps are made possible because of the infrastructure that was built in the cycles before. For example, YouTube could be built in 2005 but not in 1995 because YouTube only makes sense after the deployment of infrastructure like broadband in the early 2000’s, which happened in the infrastructure phase following the first hit dot com sites like eBay, Amazon, AskJeeves and my favorite, Neopets.

In Compounding Crazy, Packy McCormick made the case for how the rate of progress will continue to compound, citing, among other factors, the compounding of innovation.

Humanity has spent its whole existence building things that become primitives for a future generation of builders. Every new invention is an output of centuries’ worth of innovations, and then voila, it becomes a simple, cleanly-packaged input for the next invention. Like a good API, each new invention abstracts away all of the complexity that went into its creation.

Packy then goes on to speak specifically about this manifesting in fintech:

Fintech is a clear and early beneficiary of compounding innovation. Stripe, founded in 2009 and worth $95 billion, and Plaid, founded in 2013 and worth $13.4 billion, built much of the infrastructure on top of which a new wave of fintech companies can build more easily.

Fintech infrastructure companies can create huge financial outcomes for their investors and enable the next wave of companies to build products that were previously impossible or at least very difficult, expensive, time-consuming, and imperfect. Their impact compounds.

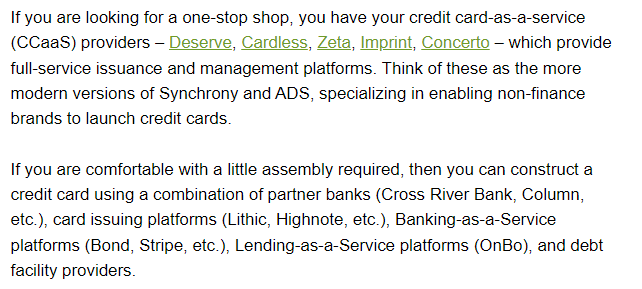

Now that we have this mental model in our toolkit, we can understand why the obstacles facing builders of applications paved the way for API-first infrastructure providers. Marqeta, for example, started as a pre-paid gift card business before moving into card-issuing-as-a-service when they realised how big the problem was for other fintechs. We’ve come a long way since then.

Ramp's own journey to becoming an $8.1 billion company in three years wouldn't have been possible were it not for the advancement in fintech infrastructure APIs that abstracted away the complexity of compliance, integrations, and all the other rigmarole of being a fintech.

This narrative of the post-GFC flowering of fintechs in the US is not too dissimilar to what took place in the UK, where a top-down set of policies and regulations were the primary drivers for London becoming a global fintech hub.

Frenzy and introspection

As students of technology waves, we all yearn for tested frameworks and lenses through which to analyse them. Venezuelan scholar Carlota Perez's work is perhaps the most frequently cited in Silicon Valley (n.b. she is working on her next seminal contribution, this time in climate change). Alex Danco masterfully leveraged Perez’s framework in a compelling argument for why the time had come for venture debt as a financing instrument for SaaS businesses, characterising it as recurring revenue securitisation. How can we leverage her framework to think about fintech?

Carlota Perez's framework is the result of analysing five different technology shifts and the phases of their development, bifurcating these into the initial Installation Period and the subsequent Deployment Period.

Within the Installation Period we have irruption:

The irruption phase consists of intense funding of innovation in new technology that yields not only new inventions but entire industries that disrupt bulwark businesses that had before seemed invincible. In this phase, new inventions also yield the development of new infrastructure.

Followed by frenzy - we know that the GFC was a catalyst for the fintech revolution that followed. We've also established that this culminated in the heady heights of 2021.

The frenzy phase ushers in a wave of speculation as financial capital, afraid of missing out, rushes in to capitalize on the new, adjacent possibilities created in the irruption phase.

Financial innovations in the frenzy phase are often the output of new theories and metrics for valuing assets, whose prices have begun to look very expensive against older metrics of fundamental value.

Reflecting on the last two years, it's clear that a frenzy took hold of fintech. The pain being felt now is probably going to continue for some time; valuation corrections are but one consequence, profligacy is being punished as well. Founders who were previously told to exhaust cheap capital as fast as possible to find product-market fit are now extending runway and prioritising unit economics, sales efficiency, and scalable acquisition channels.

If we’ve had the frenzy, are we in the Synergy phase? Will large fintechs follow the way of Big Tech (Amazon, Apple, Google) whereby the big winners of the irruption phase are so monopolistic that regulators have to step in to ensure healthy competition? Or perhaps we’re on the cusp of a wave of consolidation?

Are we really there, though? Let's think about it.

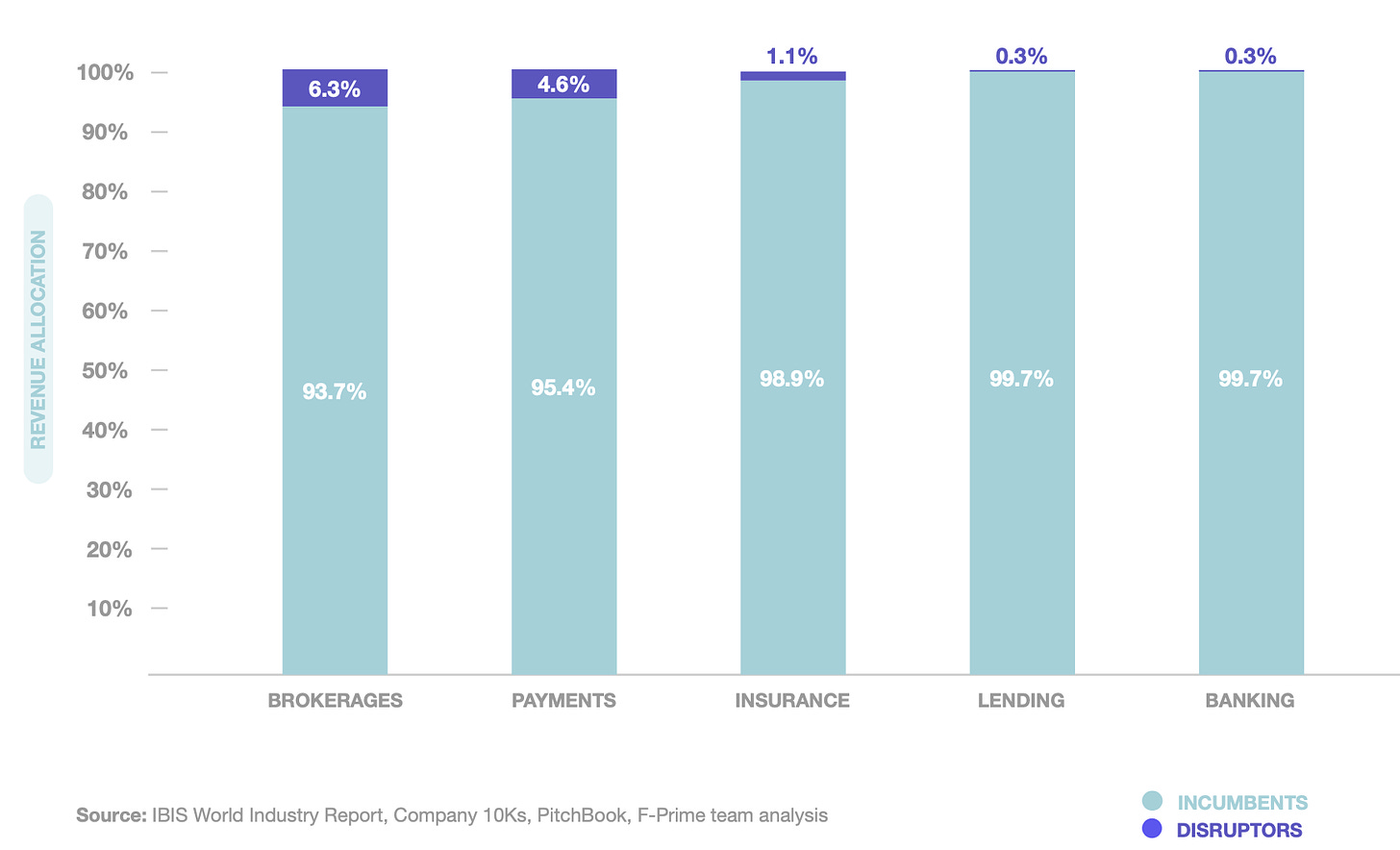

Yes, fintech has achieved a lot in the last decade and a half, but it's easy to lose sight of the sheer size of the financial services industry and how many problems persist for consumers and businesses alike, with the enabling infrastructure that needs to be built to serve applications tackling those problems.

The financial services industry is worth over $20 trillion, with intermediaries accruing $5.5 trillion in revenues..

Venture-backed fintechs have barely cracked the surface, as the penetration levels show. As I write this, Simon Taylor of Sardine and 11FS has published a case for the massive untouched TAM in global transaction banking and B2B payments.

That’s the big picture.

Let’s borrow another principle from Packy that inspires confidence, that of idea legos:

Ideas can build on each other like legos, just like software. Ideas are composable.

Composability is just software building on other software.

A new idea, built on a long chain of older ideas, can quickly combine with software that’s been composed of other software and go live within weeks or even days. That project gets to market quickly, teams up with memes and money, spreads, and its technical and conceptual components become new building blocks themselves, waiting to contribute to the next idea.

The financial services landscape is in constant flux and new lego pieces are being built all the time. Take the example of Real-Time Paychecks from Ayokunle Omojola where he describes how the combination of advances in real-time payments (RTP) with payroll APIs (which themselves were a new type of enabling infrastructure that broke down the silos of payroll data) enables the streaming of salaries on a daily basis :

I genuinely think this is the holy grail of consumer banking. It would require a significant amount of coordination between payroll providers like ADP, payroll linking platforms like Pinwheel, and consumer banks like Cash App and Chase. But once one major player adopts this, basically 100% of the industry has to adopt it, because any consumer that’s not somehow cross-sold (eg using checking + mortgage on Chase) would be at huge risk of churning to a competitor that does offer real-time paychecks via risk, low cost advances. The other reason it’s a gigantic opportunity is because it affects almost 100% of working age adults.

Infrastructure begets applications. Applications beget infrastructure. Repeat.

We'll borrow one more crisp nugget from Packy on the importance of API-first companies:

That leads to one of the most important things to realize about API-first companies: they’re a lot more than just software. Anything that just takes complex code and simplifies it is probably at risk of being upstreamed by competitors or new entrants. The magic of companies like Stripe and Twilio is that in addition to elegant software, they do the schlep work in the real world that other people don’t want to do. Stripe does software plus compliance, regulatory, risk, and bank partnerships. Twilio does software plus carrier and telco deals across the world, deliverability optimization, and unification of all customer communication touchpoints.

After internalising that, you can imagine my excitement when I saw GGV Capital announce their API-First Index to track the 50 top API-first private companies.

We are going all-in on API companies because they will fundamentally simplify software development. APIs will allow developers to offload lower-value and time-consuming components of application development so they can focus on higher-value work. For example, instead of a company asking its developers to spend months writing code to accept payments for its software, they can get up and running quickly with Stripe. For authentication, they can use Auth0. For chat, they can use Stream.

23 of the 50 companies were fintech or insurtech API providers. 46%. Many of these companies are powering the secular trend of embedding financial services in software platforms, running across the financial services gamut from cards, brokerage, crypto, lending, accounts, and more.

Final words

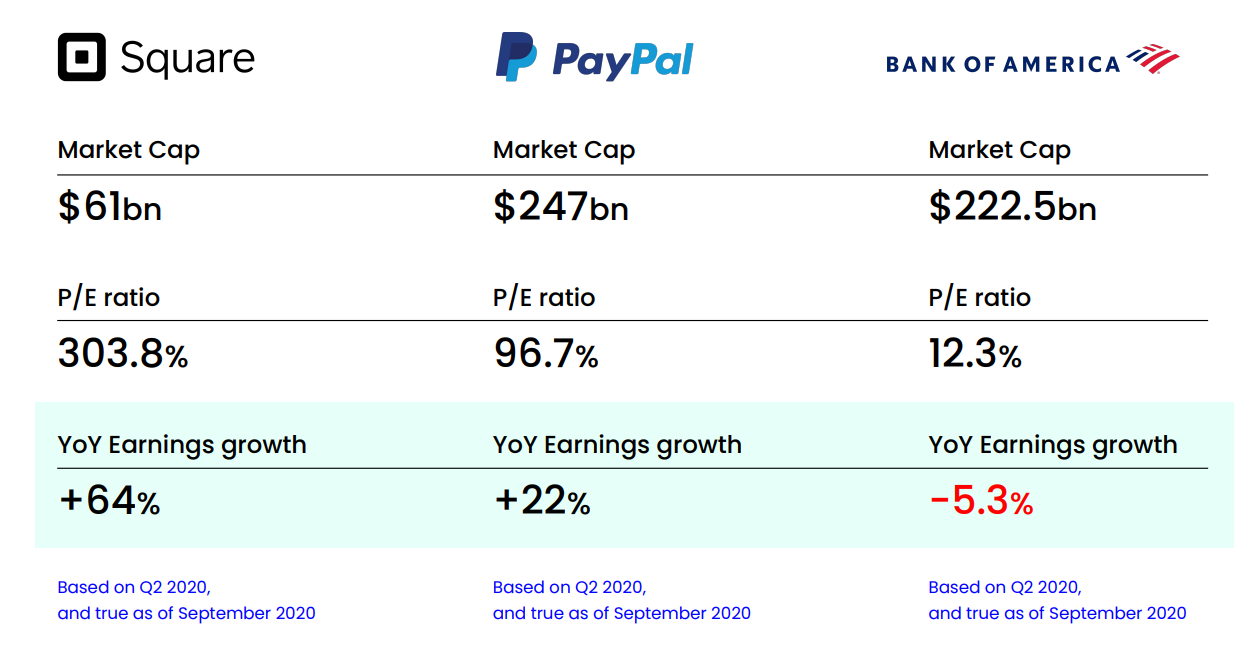

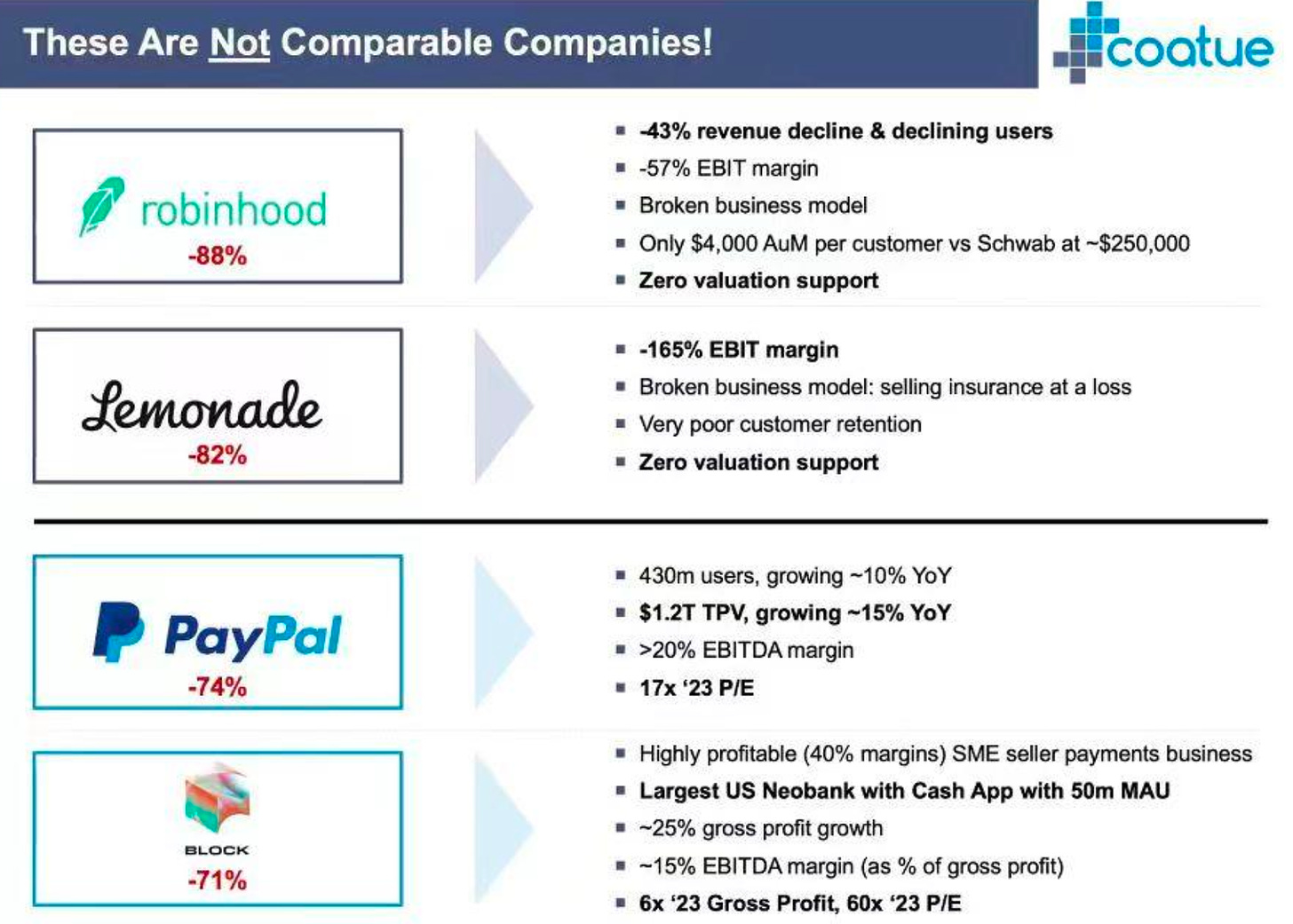

It's earnings season and we saw PayPal, Robinhood and Block announce their Q2 2022 numbers, all beating estimates. Coinbase, Marqeta, Nubank and Adyen are to follow, but the initial signs are that fintech is more than capable of producing enduring businesses with sound fundamentals (and not all fintechs are comparable, as Coatue would argue).

It would be remiss of me to discuss fintech’s future without mentioning DeFi, which is fundamentally rewriting the back-end software and rails that financial services run on. Smart contracts have the potential to meaningfully eat into the $5.5 trillion pie captured by intermediaries and simultaneously deliver significant improvements in accessibility, price, and performance.

I’ve not touched on the flowering of fintech in emerging markets. To give just a taste of how rapidly these markets are growing, Nubank managed to hit one million crypto users in one month, a feat it initially expected to take one year. Vietnam, India, and Pakistan have ranked top of Chainalysis' crypto adoption index, which speaks to the nuances and idiosyncrasies in these markets relative to developed economies (this deserves its own series of posts).

So, are we ready for more irruption?

The capital is most certainly there. The talent is there. Not only are alumni mafia forming across fintech scale-ups à la the PayPal mafia, but the ambition levels are even higher, as Rex Salisbury pointed out.

Finally, the opportunity is most definitely there. I think we're ready. If you’re building in fintech, please feel free to reach out.

Thanks to Ming You See, Ashish Aggarwal, Johnson Yang, Aika Ussenova, Ryan Zauk, Jenny Johnston and Yvonne Bajela for their invaluable feedback and comments.