Hey friends, I’m Akash!

Software Synthesis analyses the intersection of AI, software and GTM strategy. Join thousands of founders, operators and investors from leading companies for weekly insights.

You can always reach me at akash@earlybird.com to exchange notes!

OpenAI’s wider release of Sora last week revealed more about how they intend to win: becoming a product company.

AI’s Amorphous Stack

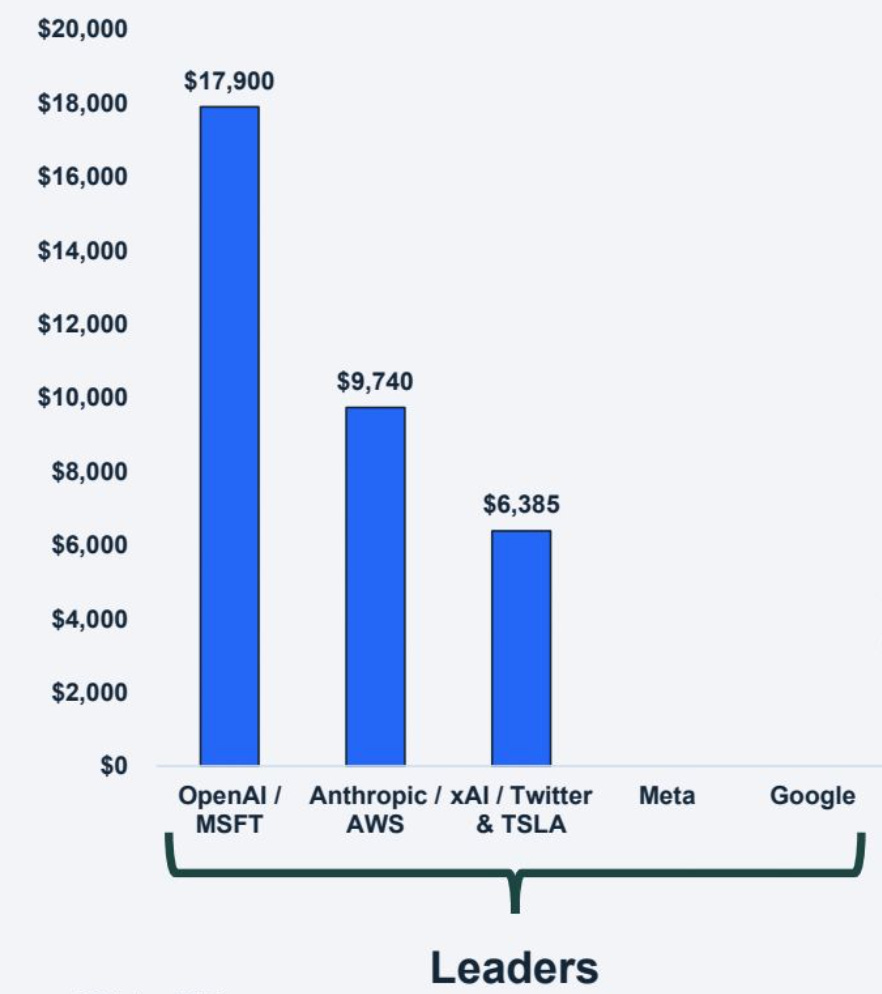

Two years into the AI revolution, the ecosystem has consolidated around five research labs, each with a distinct superpower - from brand to talent, and data centre construction to vertical integration.

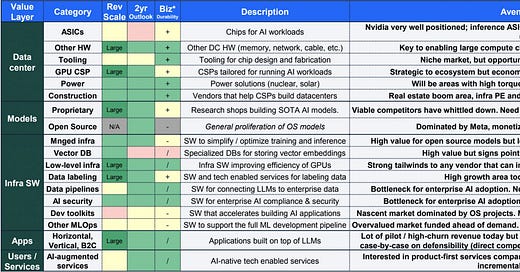

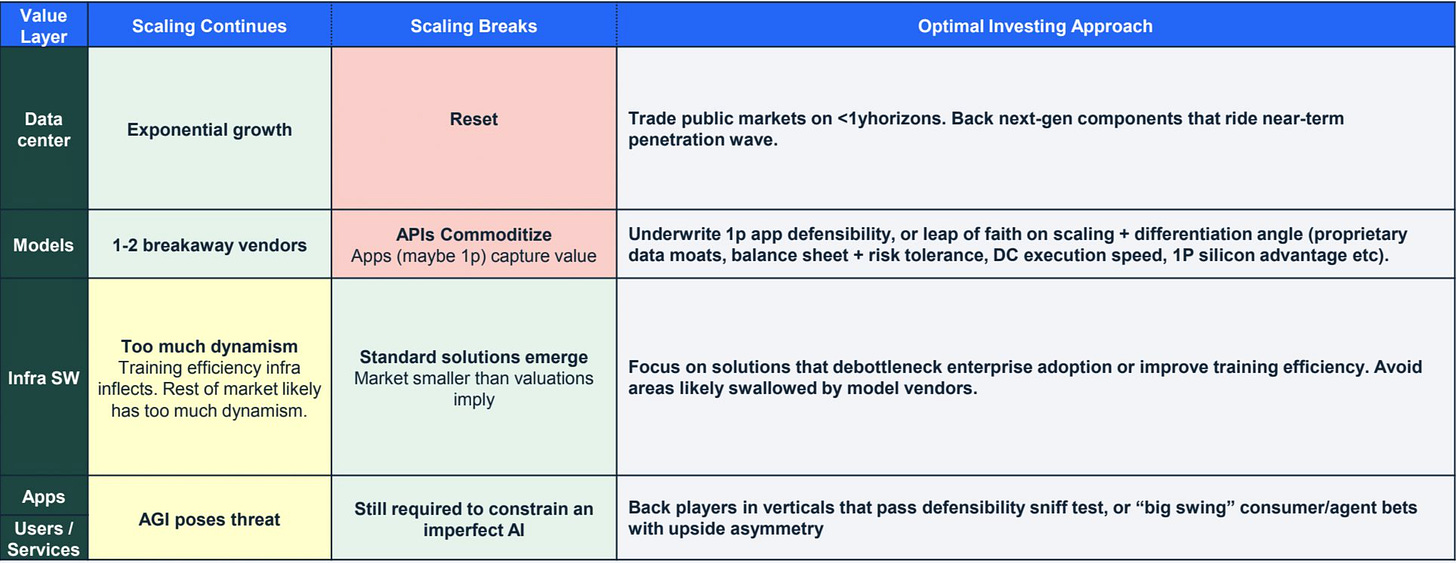

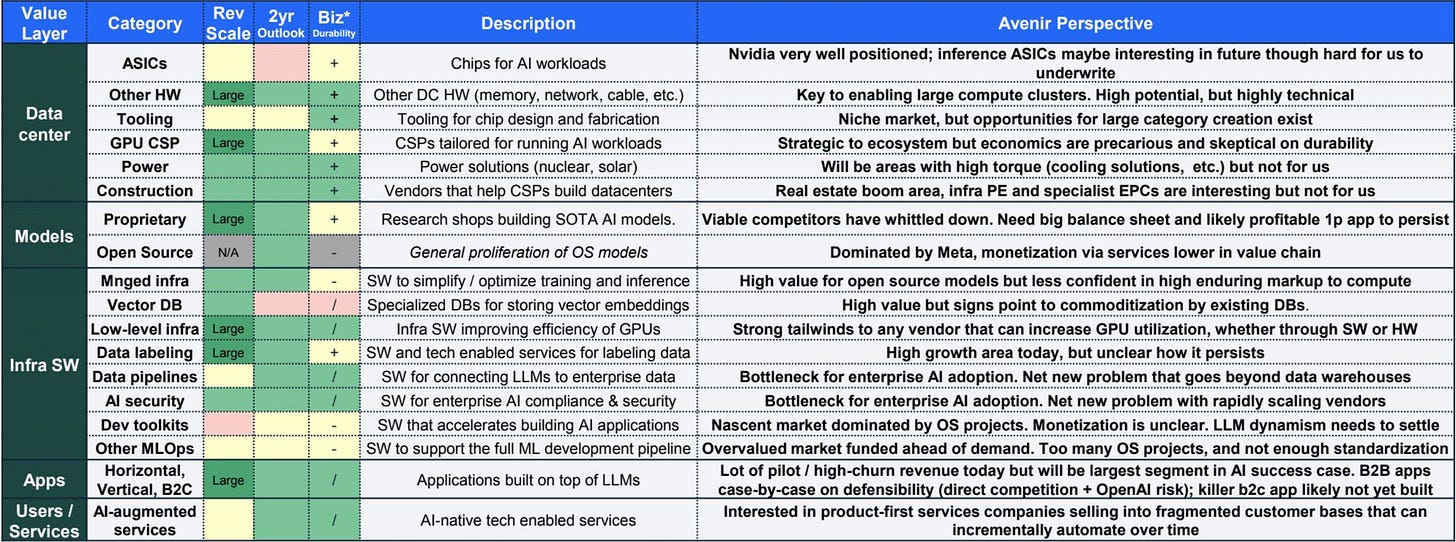

Analysis of value accrual in the AI stack has taken on the new dimension of dependence on scaling laws (whether they hold or break) - see the excellent report from the team at Avenir here.

As Meta continues to commoditise its complements (with AWS joining the model commoditisation efforts at re:Invent) by open sourcing frontier model capabilities, proprietary model builders are becoming product organisations and shipping first party apps to become antifragile with respect to scaling laws.

This review of Sora from Every’s Dan Shipper is consistent with OpenAI developing first party applications on top of their models.

“OpenAI is trying to have its ChatGPT moment with video.

When they initially launched Sora, I think we all assumed that it would be released as an API—at least at first. That’s been the historical trajectory of all of their products to date.

But with Sora, OpenAI opted to build the beginnings of a full end-to-end creative suite for video.”Vertical Integration

Developers may follow the rotation of frontier models on leaderboards, but Apple’s victory in mobile decisively answered the question of how consumers place a premium on the convenience of vertical integration.

The issue I have with this analysis of vertical integration – and this is exactly what I was taught at business school – is that the only considered costs are financial. But there are other, more difficult to quantify costs.

Modularization incurs costs in the design and experience of using products that cannot be overcome, yet cannot be measured. Business buyers – and the analysts who study them – simply ignore them, but consumers don’t.

Some consumers inherently know and value quality, look-and-feel, and attention to detail, and are willing to pay a premium that far exceeds the financial costs of being vertically integrated.

Ben ThompsonVertical integration decisively won mobile, and eventually the PC industry too.

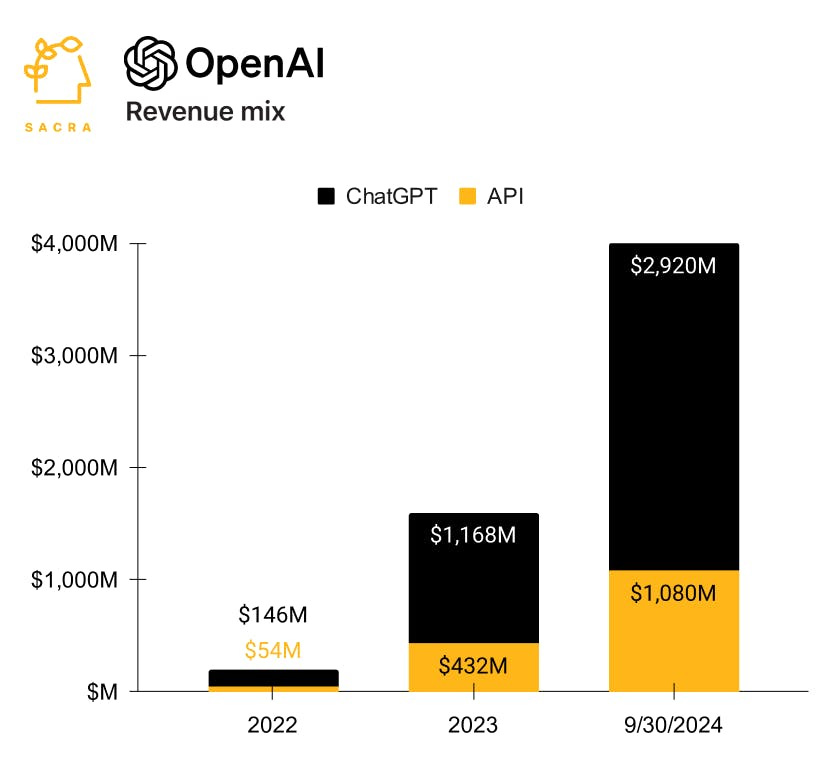

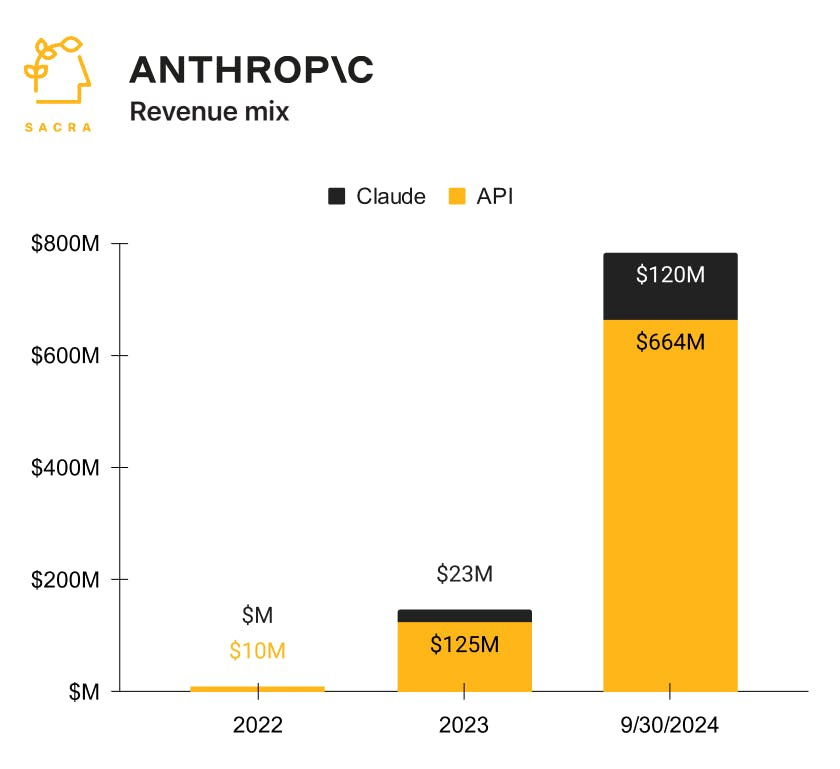

Thus far in AI, leadership in product rather than model capabilities is what’s translating to consumer mindshare and revenue:

Here’s Ben Thompson again, speaking about the superiority of ChatGPT’s Mac app versus Claude 3.5 (citing features like web browsing, integrations with other apps):

Isn’t the point the intelligence, and isn’t Claude better?

I mean, maybe, but for me AI is a tool, and part of the usefulness of a tool is its ergonomics, and ChatGPT is just flat-out better; I want to use it because it’s nice to use, and I can’t say the same for Claude.

Yes, this is a very “consumery” take, but, well, this is part of how OpenAI pushes its massive lead in consumer mindshare!Anthropic’s appointment of Instagram cofounder Mike Krieger as CPO demonstrates their ambition to become as strong in product as they are in research - the ongoing investment into Computer Use is another sign.

Lessons from Big Tech

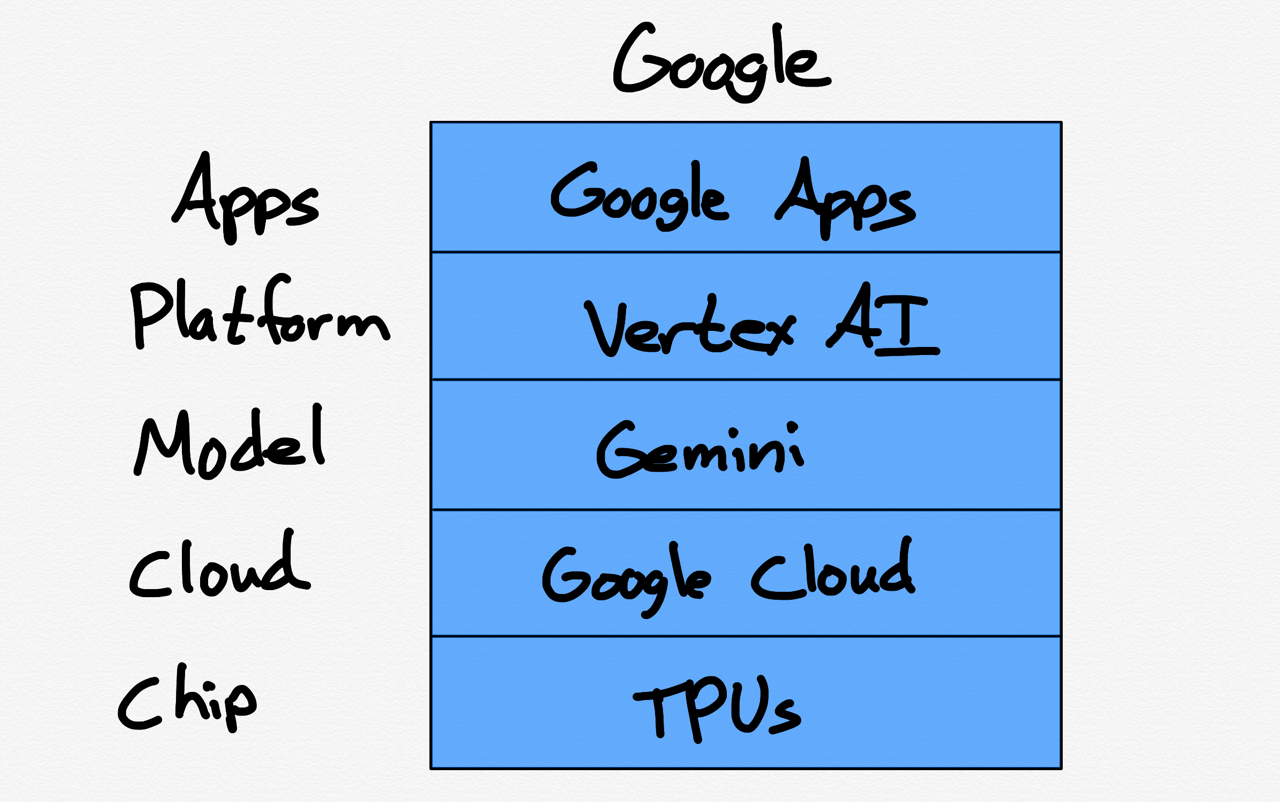

Google is often cited as the most vertically integrated company in AI, from their own hardware (TPUs) and data centres all the way up to the Gemini models, Vertex, tooling via GCP, and a suite of apps.

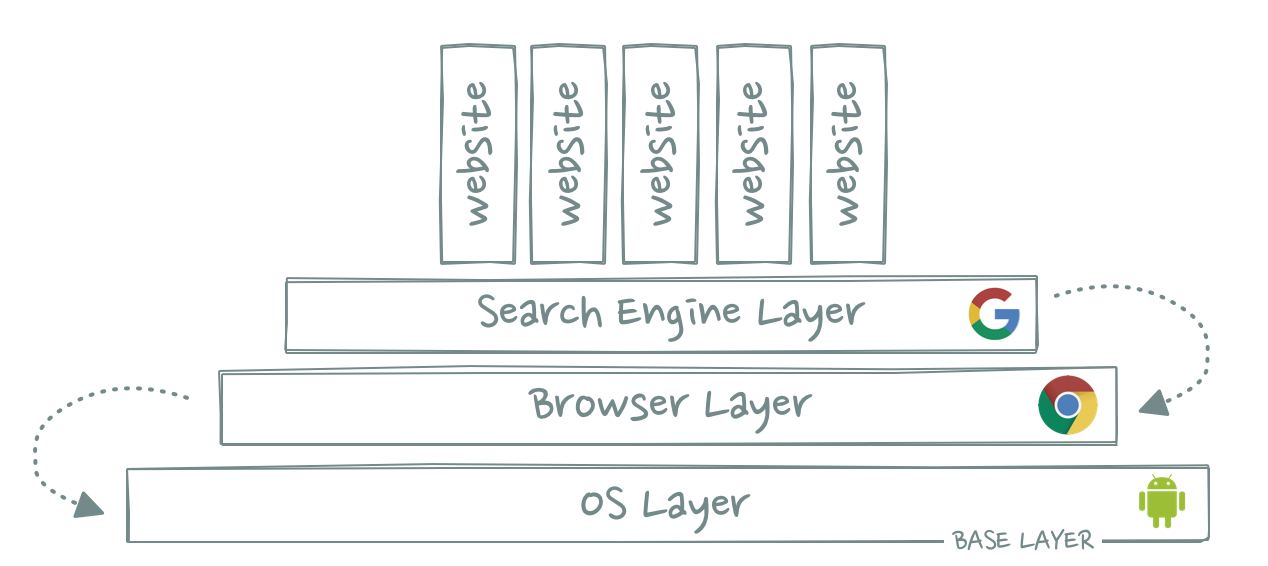

Google’s strategy in the internet and mobile shifts is instructive - starting with their search engine product, they moved closer and closer to becoming the default for end users through Chrome and Android.

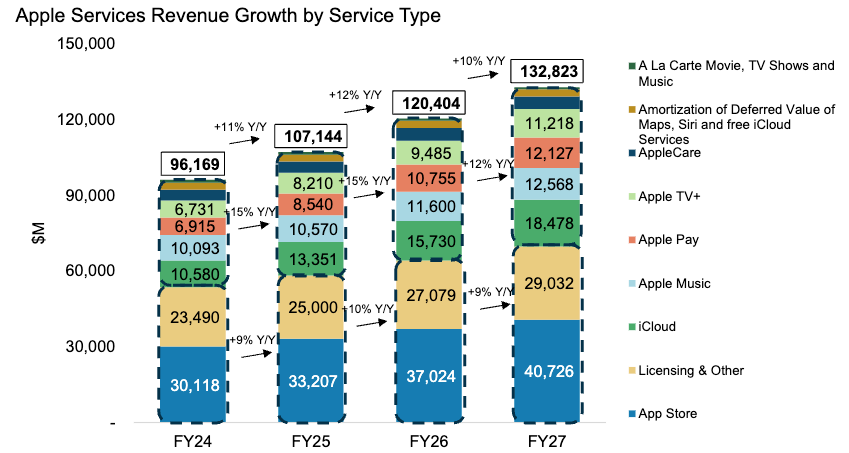

As far as advertising dollars go, however, Apple’s vertical integration ended up winning over Google’s, given their market share with affluent consumers.

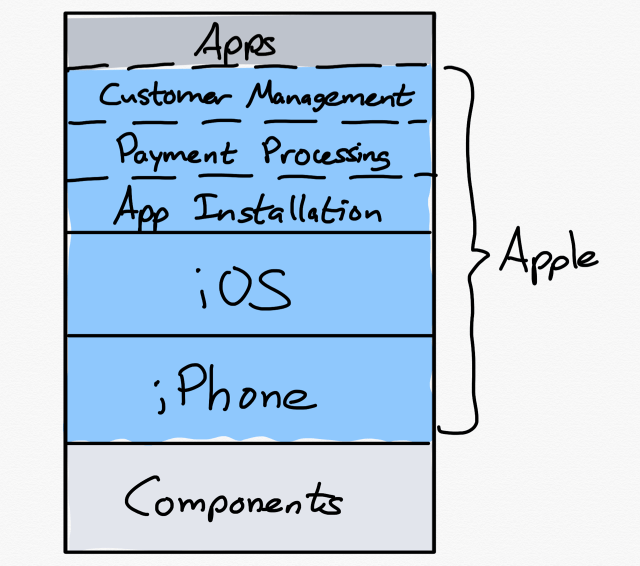

In this platform shift, Apple realises its role in the AI value chain as one of an aggregator. First party AI apps might come later, but for now Apple Intelligence will primarily play to Apple’s strengths: your iPhone knows more about you than anyone, and Apple’s AI inference handles this data in a way that preserves privacy. App developers seeking to access Apple’s customers will need to acquiesce to their demands to expose data for Apple Intelligent to become more capable over time.

Google of course already has its first party apps, its own models, and its own chips - it ought to be well positioned to realise the advantages of their vertical integration by distributing Gemini through Chrome, Gmail and Google Calendar.

Rumours about Google doubling down on the Pixel phone hold just as much weight as Apple working on their own search engine - not much.

There’s a key lesson, though, in how the iOS + iPhone combination won over the purely financial argument for modularised combination of Android + XYZ heterogenous device manufacturer.

The tight coupling of hardware and software allowed Apple to forward integrate into the application ecosystem and deliver the best user experience, period. The app store, the $15bn licensing deal with Google, and Apple Pay were all propelled by tailwinds as Apple established itself as the trusted counterparty for consumers transacting and interacting on the internet.

Apple’s own first party apps are a different story, relying on the power of defaults rather than getting anywhere near parity with Spotify on the product and experience (as for Apple TV, the signs don’t look good).

Even so, the main lesson is that the best products and user experiences matter. Apple’s vertical integration of their OS and hardware helped them win consumer share of wallet, whereas Google parlayed the dominance of PageRank into owning layers closer to their customers (Chrome, Android).

AI Startups and Backward-Integration

Over time, Apple backward-integrated into components by producing their own chips. This strategy laid the foundations for AI on the edge, which could end being a key factor for a bigger iPhone upgrade cycled spurred by Apple Intelligence.

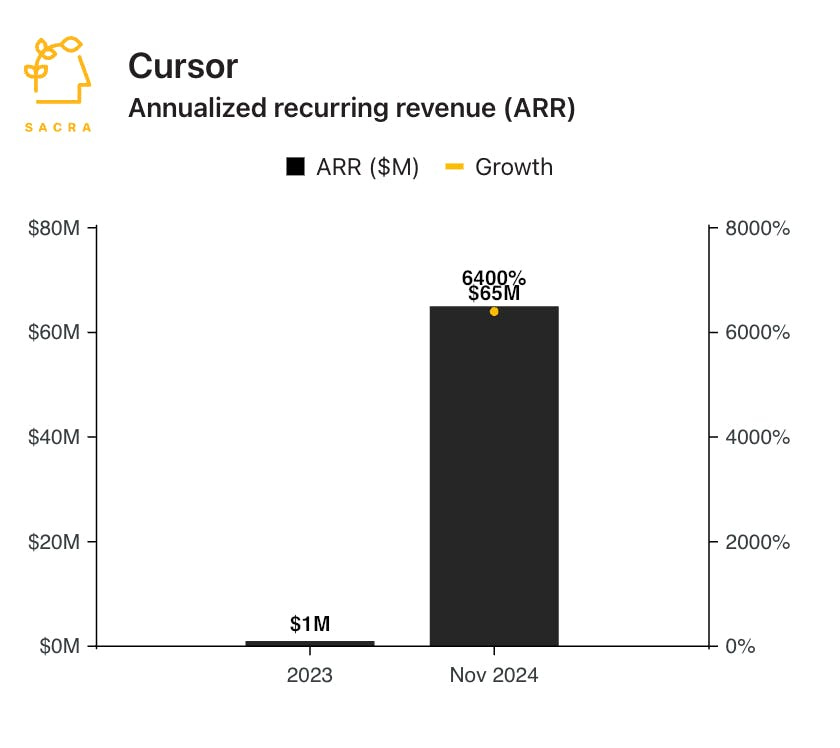

As Anysphere secures a new round of funding at a rumoured $2.5bn valuation and $50m ARR, Cursor’s relatively unique path to get here deserves attention.

Where other companies raised hundreds of millions to build code generation foundation models, Cursor took off the shelf models and build the best product for developers (autocompletions, suggested edits).

As my friend

has written, where developers could previously attribute more than half of Cursor’s value to the underlying third-party models, the company is well funded to flip that ratio by developing their own models.The sequence they did it in, though, matters. They have developer mindshare.

Granola is another example of a successful AI application that has validated different hypotheses about what an AI-native product should look like. The retention is incredible and the user experience is magical. If Granola were to seize this momentum and unlock more funding in order to backward-integrate to lower levels of the stack, they’d be better positioned to do so having secured distribution and mindshare.

The distribution advantages Big Tech enjoy stem from the kinds of product and UX innovations that AI startups are more than capable of delivering in this new paradigm. Once an AI startup achieves a certain threshold, they are well placed to backward-integrate into infrastructure, models and potentially hardware.

The exact evolution of vertical integration and modularity will vary across the modalities. Aside from text, ElevenLabs, Runway, Kittl, Photoroom and Synthesia are examples of companies that are both model and product companies. Stable Diffusion, Mistral, AI21 are a few of the pure model companies.

Thank you for reading. If you liked this piece, share it with your friends, colleagues, and anyone that wants to get smarter on company building.